Base layers: Clothes For Multiday Hiking Part 2

Choose the right base layer to keep you dry, warm or cool: not too hot and not too cold but just right!

Red Ottie merino base layer tee, blue fleece jacket, black shell rain pants in the infamously changeable weather of the South Coast Track, Tasmania.

In Part One, we considered what kinds of clothes are best for hiking, and why the most expensive items are not necessarily the best. In fact, although many of our examples are familiar hiking brands, by clever shopping and learning to understand labels you can find suitable clothing in all kinds of shops, not just outdoor ones: search out bargains online and in second hand shops, in KMarts and in Aldis. When you understand the foundational principles of the layering system and materials, you have the key to choosing correct clothing. The closest-to-skin one is the base layer.

Here, you’ll find everything you need to choose the right base layer for you. As always, we cover a wide range, canvassing the advantages and disadvantages of each, so that you can select to exactly fit your climate, hiking style and budget preferences.

This article covers:

1. The Layering System: A Recap

2. Materials (characteristics, pros and cons):

Synthetic

Natural (wools, silk, fibres)

Hybrids (lyocell/Tencel/bamboo)

merino blends

Knit weight (gsm)

microns

Treatments (Stink, Insects)

3. Design

Form-fitting or loose (thermal base layers, polos, hiking shirts, thermals)

Mesh and open weaves

Thumb loops

Neckline

Offset seams

Length, sleeve length, droptail

Vents and panels

The Layering System: A Recap

Multiple layers in New Zealand. Geoff now wears a much lighter fleece insulation layer because this one is overkill on a multiday hike, and very heavy to carry.

Multi-function jackets are usually thick, heavy, insulated, with a plethora of pockets, and are supposedly “waterproof.” This one jacket, you think, will do everything! Keep you warm, dry, and it’s just ONE item!

But that very sales pitch – usually aimed at city commuters – is exactly what makes these jackets terrible for hiking. They are perfect when you get up in the morning but, as soon as you begin walking with a pack, they’re too hot. When it rains, water wets the padded insulation: after an hour, you’re drenched. Or, the jacket doesn’t leak but it doesn’t breathe either, so becomes leaden with sweat.

The layering system is considered current best practice for outdoor activities like hiking. It varies somewhat between activity type, but the principle is a modular system of clothing that you mix and match to suit conditions. Unlike a single jacket, the system comprises a minimum of three (but up to five) layers that keep you cool or warm and/or dry as need be to maintain your normal body heat: shedding it during exertion, and preserving it when temperatures drop. You mix and match these thermoregulating layers to suit different climates or changing weather throughout the day.

The system is based on three layers:

Base

Insulation/Mid and

Shell.

Closest to your skin is the topic of this post, the base layer, either long-sleeved or short sleeved, plus optional long bottoms to wear under or instead of pants/shorts. It is usually – but not always – relatively form-fitting, and its primary aim is to move moisture away from your skin to keep you dry from sweat, and hence warmer in cold weather. Base layers let moisture leave your skin by allowing sweat in the form of liquid or vapour to pass through or into them, rather than being trapped on your skin or on the surface of the garment fibres. Some of it is wicked away, but a lot of it passes through as vapour.

Although many people consider a thermal base layer a dedicated garment worn under something else, the base layer for hikers is whatever layer you have closest to your skin, be it a thermal base layer, a merino or synthetic tee, a sun hoody, or a hiking shirt. In this article, we’ll distinguish between thermal base layers that aim to add warmth whilst keeping you dry, and other base layers such as tees, sun hoodies or hiking shirts that regulate temperature primarily by keeping your skin dry.

The next layer is your insulation or mid layer. The primary aim of this layer is to keep you warm. It also breathes well, so that the moisture that has passed through the base layer continues to pass through without condensing or soaking in.

Are we having fun yet? A rainy day on the South Coast track, but we are dry inside!

The outer layer is the shell. A shell is waterproof and almost always windproof. The purpose of the shell is to keep you dry from rain, snow or sleet, and usually also to prevent windchill.

These three modular layers can be mixed and matched for most conditions while you are on the move. Wear just the base layer if it’s warm. Add the mid layer if it’s cool. Add the shell if it’s cold, or raining. If you’re hiking in rain but it’s not cold, wear the base layer and shell without the insulation. You can immediately see how these three layers are more flexible than a single thick insulated jacket worn with a base layer.

Many people carry a fourth layer, or use a combination for their insulation/base layers – ultralight down puffies, sun hoodies and wind shirts are three popular additions or alternatives.

Base Layer Materials

Geoff a decade ago in an old synthetic baselayer tee that he once used for hiking, but which is now relegated to the gym because he prefers merino.

Many other hikers prefer synthetic.

Base layers are either synthetic, natural, a blend, or hybrid fibres in a range of different knits and weights. Because the primary purpose of a base layer is to keep your skin dry, its ability to absorb, wick and/or allow liquid water or vapour to pass through is crucial to its efficacy. This can be how easily (hydrophilic) or poorly (hydrophobic) it absorbs or wicks liquid sweat, or how much sweat it adsorbs as vapour (hygroscopic aka hygrophilic). To complicate matters, the surface of a fibre (wool, silk) may be hydrophobic, whereas the inner of the fibre may be hygrophilic. This means that a wet garment doesn’t feel cold and clammy even when it absorbs moisture, because the outside of the fibre remains dry.

A tighter or more open knit or weave, different fibre deniers and fabric thicknesses, gridded or patterned weaves, and blends with other fibres amplify or mitigate desirable or undesirable qualities respectively, sometimes more so than the type of fibre itself. So a very light, open knit of a less breathable or wicking fibre can be more effective than a standard knit of a more breathable/wicking fibre.

Base layer Denier and Weight (GSM or oz/yrd)

You’ll often see base layers – especially natural fibre base layers – described in their fabric weight, with gsm (grams per square metre, or oz per square yard for US readers) being the standard metric measure (conversion here).

The gsm of a baselayer is determined by the yarn or fibre’s denier (the weight of a single strand of a certain length of fibre/yarn), as well as how those strands are knitted, woven or combined, with more strands or tighter weaves creating heavier garments.

Women’s 125 gsm Zone Knit merino base layer (Image Credit: Icebreaker)

Polartec Powerdry 180gsm synthetic base layer. (Image Credit: Mont).

Some companies use the GSM in the naming of their product range, so you can quickly judge how warm they might be. Categories vary depending on fabric use but, in hiking base layers, the kinds of numbers you regularly see are around 130gsm for very light wool base layers (either t-shirts or thermals), less for some silk and synthetic base layers. Midweight base layer t-shirts are usually around 150-180gsm, with heavyweight hiking base layers ranging between 200-260gsm. At the upper end, wools begin crossing into mid layer territory; similarly, light synthetic fleece insulation layers can be as low as 80GSM. Merino ‘thermals’ range from 130gsm to 230gsm.

All things being equal, heavier fabrics are thicker and warmer, but all things are not equal. A mesh material can be extremely cool when worn on its own, and extremely warm when layered underneath something because of its structural ability to trap insulating air. This is how those mesh materials such as Brynje’s 140gsm polypropylene or 125gsm wool comprising primarily gap rather than strand – ie very light! – can also be astonishingly warm. And that’s why both lightweight mesh and 260gsm merino suit cold conditions.

However, mesh base layers are ideal for when you’re working up a sweat climbing hills or fastpacking, because they allow moisture to evaporate easily through all those holes. And although Polartec’s Alpha Direct mesh is usually used as an insulating mid-layer, some people use the lightest 60-80gsm weights as base layers: see Part 3, Insulation layers (coming soon) for more detail.

This screenshot from Brynje’s video on layering for very cold conditions explains why lightweight mesh is so effective. (Image Credit: Screenshot from Brynje).

Thicker fabrics are usually more durable but, again, it depends on composition: a light nylon-polyester blend may be more durable than a heavier pure merino blend. In our experience, very light (130gsm) pure merino knits are fine for day hikes but quickly develop holes and ladders when worn under a framed pack; blends are stronger.

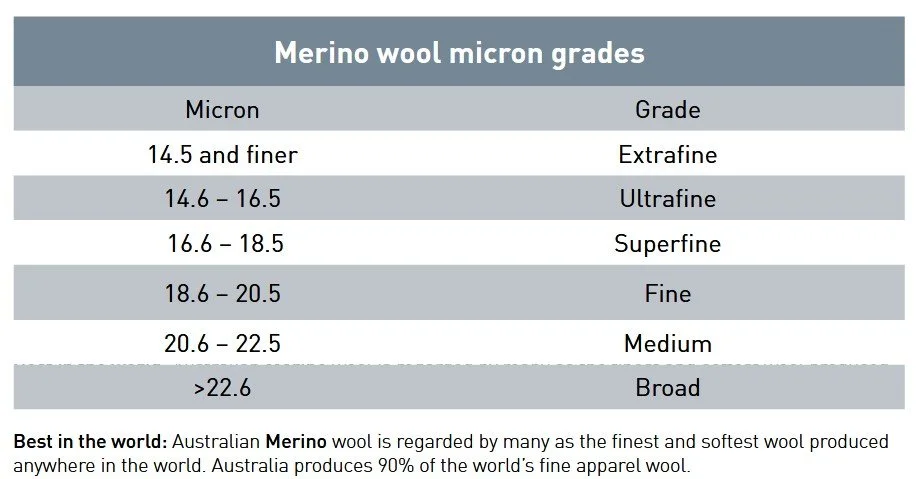

Microns(µm) and Micron Count

The diameter of an individual strand of wool/hair is measured in microns (µm), where 1 micron = .001mm. The fineness of a wool used in a garment is measured as its micron count, and anyone who has ever worn an itchy childhood jumper knows why it matters! The roughness of the scales on individual fibres makes a difference too, with smoother smaller scales being less irritant. I still remember hives on my neck from a hand-knitted jumper: ugh! Those memories are so powerful that many adults never consider wearing wool against their skin ever again.

This is a shame because Australian merino wool base layers are now so fine and well-processed that most people no longer find them itchy. Here is a table:

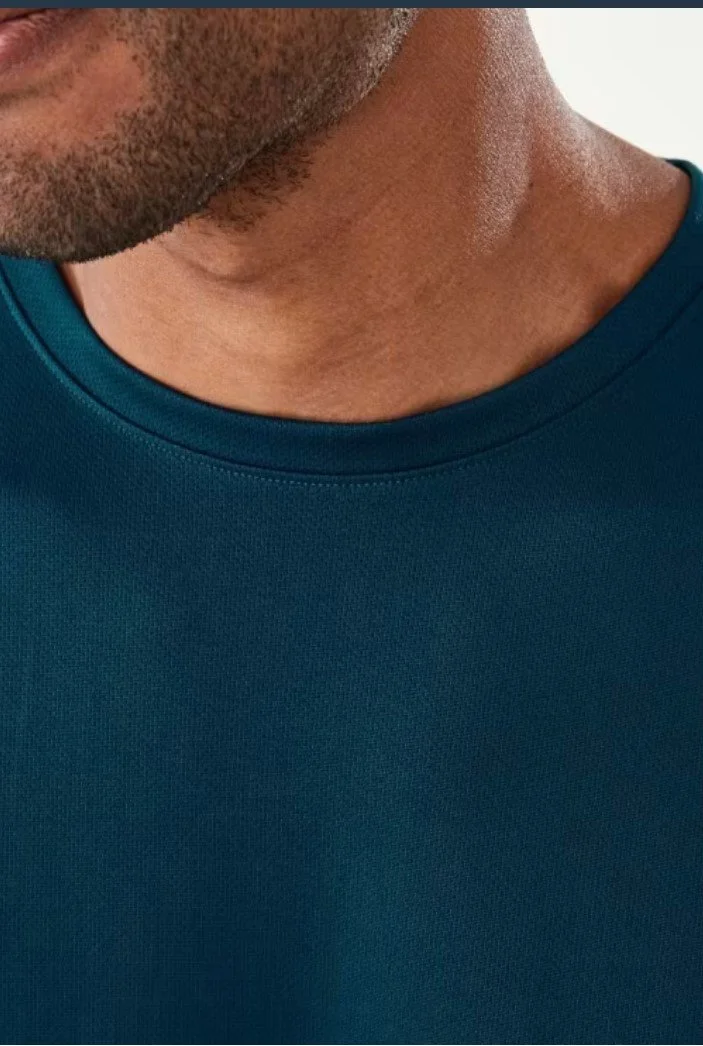

Merino wool, compared to ordinary wool, is under about 23µm. A quick perusal of the more widely available merino base layers show most are in the superfine range around 18.5 µm, with a few (expensive) outliers such as Icebreaker’s MerinoFine™ 15.5-micron merino in the ultrafine range. However, beware: when you check the numbers, some other thermal brands labelled ultrafine are actually in the superfine category; this won’t matter to most people but could for those with sensitive skin. If this is you, you may do better with synthetic base layers, unless you want to empty your wallet.

Men's 150 MerinoFine™ Ace Short Sleeve T-Shirt may suit those who are particularly sensitive to wool.

(Image Credit: Icebreaker)

Knit Quality

If buying wool base layers, we discovered through experience that knit quality as well as weight makes a huge difference to both durability and softness against the skin. If choosing merino base layers, those with a little spandex/elastane may retain their shape better after multiple machine washes, but a good knit can do the same.

Ottie Merino tee (Image Credit: Ottie merino)

Sometimes clothing brands start out great but suddenly deteriorate when they expand and/or move manufacturing to a different factory or country; Geoff and I noticed that two brands we own that are ten years old developed fewer holes and ladders than much more recent releases. Conversely, Australian Ottie Merino tees at 18.4 µm and 165gsm, while not much different numerically to our other tees, are the softest, smoothest merino base layers we’ve ever worn and they have far, far outlasted our Icebreaker and MacPac tees of similar weight (newer designs may differ).

My three-year-old-green Ottie tee, still worn almost weekly at home year-round as well as on many hikes to assess durability. This tee has just one small hole on the upper back where the pack frame rubs aginst a bra buckle, and it has never laddered. It still retains its shape (the person inside less so!).

The same cannot be said for several other brands in different knits, or in different fabric weights. The slightest hole turns into this.

Ottie tees are expensive and we rarely recommend specific brands, but we have been extremely impressed with this cottage company’s t-shirts (we have no financial or personal affiliation with them and have bought all our tees and thermals at full price).

Synthetic Base Layers

Synthetic base layers comprise woven or knitted plastic fibres derived from petrochemicals. In factories, a liquid solution of the plastic compounds is extruded through tiny holes to form long fibres.

Hilary writes of her polypropylene: “At the age of 64, I hope to pack in lots of walks over the next decade. Gear? Well, I pulled out the ancient thermals, decades old, and wore them under my shorts and jacket as required. They were old, pilled, stained, and they were brilliant. On this day, I also wore long thermal pants for the predawn start from Oturere Hut (see the torch around my neck), but easily removed them as I warmed up. The sleeves on the thermals can be pulled up and down as required, and I don't have to worry about tearing from branches and rocks, as I would with my precious merino. (Image Credit: Hilary)

We older readers remember the cheap – but infamously stinky! – stripey polypropylene and it is still widely available because it absorbs almost no water and is incredibly cheap, so remains the best baselayer for those on a budget.

However, many newer synthetics, usually polyester or nylon, are treated or coated to make them more odor- and/or water-resistant; some are impregnated with permethrin to help protect against ticks and other biting insects. They still don’t come close to natural fibres in stink-resistance, but they are cheaper and absorb less (sometimes zero) moisture, so dry faster. Those who prefer synthetic base layers generally do so because they wick so quickly, dry so fast and absorb so little sweat.

Polyester is one of the best synthetic base layers. Unlike many natural fibres, polyester is hydrophobic and absorbs almost no water or water vapour: moisture doesn’t get inside the fibres. That’s why you can blot or spin dry lightweight polyester hiking clothing, and it is dry enough to literally wear immediately. Polyester base layers breathe and wick well, hold their shape without stretching or shrinking, are cheap, and are moderately durable and resistant to abrasion.

You can buy expensive brand name polyester, or go to your local budget chain and read labels:

KMart men’s active mesh polyester t-shirt, just $5.50 at time of writing!

(Image Credit: KMart).

You’ll see polyester in many different forms and branding, from Polartec Powerdry thermal baselayers (145-160gsm), Montbell’s Zeoline, Patagonia’s Capilene and dozens more: they might have different names, weights, knits and/or weaves, but all are polyester. Many insulation fleece layers are polyester.

My 10 year old synthetic tee is an interesting mix of panels of different materials. The front is 100% polyester. The polyester on the front and sleeves is a finer knit because the material already has excellent wicking properties.

The back and underarms are a blend of 55% nylon and 45% polyester. Under a pack, this makes your back sweatier, but the material is more durable to abrasion. To mitigate nylon’s clamminess, the blend is an extremely lightweight gridded knit with tiny holes. Once you understand the why and how of such materials and knits, you can assess how the garment will function.

Unlike polyester, nylon can absorb 3-10% of its weight in water, though the surface of the fibres is initially hydrophobic. Nylon doesn’t breathe as well as polyester and is therefore more likely to trap moisture, so it can feel clammy when wet. However, depending on weave/knit, it is softer on the skin, cheaper, and more durable, so it’s often blended with polyester.

I wore a 72%Nylon 28% elastane shirt on the Tour du Mont Blanc. It was clammy, sweaty and stinky and I never used it again on any hike. However, in loose-fitting garments such as hiking shirts band pants, the durability of nylon and nylon-polyester blends can work realy well.

Natural Fibre Base Layers: wool, hair and silk

Our current preferred base layer after trying many different ones is merino. YMMV and that is okay (HYOH, ie Hike your Own Hike)!

Natural wools and fibres are much more expensive than synthetic ones, but hikers often prefer the feel of them against the skin, plus their vastly superior resistance to becoming stinky.

Merino is the natural fibre of choice for many hikers. It absorbs 30-35% of its weight in moisture without feeling wet because, although the inside of the fibre is moisture-loving, the outside is hydrophobic to water in its liquid form. Because the outside of the fibre stays dry, you don’t feel clammy or cold when wearing it.

However, there’s more to it than that, because water vapour in the form of evaporating sweat is readily adsorbed (trapped) inside wool fibres, creating heat in the process. This chemical reaction is known as the Heat of Adsorption, and it is key to wool’s ability to keep you warm until it reaches about 30% of its weight in water, including in extended periods of damp.

Compare this with cotton, which astonishingly absorbs up to 27 times its own weight in water, and whose surface is moisture-loving: it’s why towels are terry cotton! Remember the feeling of wet cotton jeans: heavy, clammy and freezing especially when you add wind into the mix: the surface and your body stay wet, without insulating air gaps. We know that water conducts heat much faster than air, so the wet fabric very efficiently draws away your body heat. Now you understand how and why cotton is dangerous for multiday hiking, even though outdoor brands sell them in outdoor shops.

Silk base layers can be as light or lighter than synthetic ones. Like wool, silk can absorb about 30% of its weight in water before becoming clammy, and the structure of the fibre makes it excellent for wicking as well as trapping air. However, it is relatively slow to dry compared to synthetics.

Alpaca and yak wools have a slightly higher warmth to weight ratio than merino, but are much, much more expensive: cheap, light, warm — pick two! Some animal fibre base layers have a small percentage of elastane (aka spandex or lycra) added for durability and to better hold their shape when machine washed. You can go down multiple convoluted rabbit holes comparing different animal fibres’ warmth/wickability:weight ratio, but most give good to excellent results. It’s difficult to compare like for like because, outside the laboratory, weight, knit and denier vary so much between garments. Remember that a fibre with a lower warmth:weight ratio can be equally warm, just heavier. Most hikers prefer a marginally heavier merino base layer or a cheap but light synthetic to a vastly more expensive alpaca or yak one.

This 170gsm thermal baselayer from Dilling is designed to be worn under clothing: it definitely looks like underwear!

However, it is an interesting and practical blend of 70% merino and 30% silk, expensive for Aussies but more manageable for European locals (Image Credit: Dilling).

Although drying time is affected by how tightly moisture is held by the fibre, in real life the main influence by far is how much moisture the fabric has absorbed/adsorbed in the first place. Wool takes much longer to dry than synthetics so, although it can keep you warmer, synthetics often keep you drier: it is swings and roundabouts. Consider this if you hike a lot in wet, cold weather. Geoff and I prefer merino, but others prefer synthetic, especially on extended wet hikes.

Hybrid or Semi-Synthetic Fibres

Hybrid fibres are derived from natural cellulose or wood fibre such as eucalypt, beech, bamboo or, more recently, wheat , that is processed and produced in a similar way to extruded synthetic fibres but without petrochemicals. These synthetic fibres are known as rayon, viscose, (modal is manufactured slightly differently), and lyocell (Tencel is simply a brand). Regardless of which plant the cellulose originates from, it is the same building block. However, although solvents are used to dissolve the cellulose in all, only those for lyocell are non-toxic. The manufacture of the others also produces polluted wastewater.

Conversely, the manufacturing process for lyocell is a closed loop system: no harmful byproducts are created, and nearly all the solvent chemicals are recovered to be reused again and again. The process for lyocell is also cheaper, faster, and requires less water overall; the resulting textile is 100% biodegradable. Lyocell is therefore considered sustainable and eco-friendly: it doesn’t require the same land use as most animal-based fibres, and doesn’t require petrochemicals or release plastics into the environment like synthetics. However, a lot of fibre is wasted in the production process, so source plants must be sustainably grown.

Lyocell is extremely strong and blends well with both natural fibres and synthetic ones, and you’ll find merino tees blended with 10-80 percent lyocell, making them more durable. It is also used on its own in the same ways as cotton and silk.

Icebreaker Cool-Lite Featherlight 80% Tencel and 20% merino in an Activewear open mesh knit. Very light indeed and great for many high intensity activities, but probably not multiday hiking in Oz. (Image Credit: Icebreaker)

Icebreaker Cool-Lite 60 percent Tencel, 40 percent merino: will feel cooler than pure merino when wet and take a long time to dry. (Image Credit: Icebreaker)

Lyocell is smooth against the skin, breathable, wicks well and is less stinky than nylon and polyester so you can find, for example, pure bamboo base layer thermals because of its thermo-regulatory ability. Similarly, lyocell also feels cool against the skin when worn without an insulating layer and is therefore often blended into active wear like running tees.

However, for multiday hiking, pure lyocell has one huge disadvantage: it absorbs even more water than cotton! Cotton absorbs 27 times its own weight in water, and lyocell absorbs 50% more than that: more than 40 times its own weight in water! Although the surface of the fibres stay drier than cotton, Geoff owned a pair of bamboo socks that took forever to dry, certainly longer than any of our wool socks; on a multiday walk in extended cold, wet weather, all base layers are going to get damp. Will they ever dry?

Many hot climate hikers swear by lyocell/merino blends not least because they are promoted as being cooling, but carefully consider your specific hiking environments when choosing any base layer with a large percentage of lyocell.

Washing:

When buying base layers for multiday hiking, check washing instructions on the label. Synthetics are generally pretty straightforward. Remember LNT: few multiday hikers wash clothes on trail and, if we do, can’t use soaps or detergents in natural water sources. Some people use a wash bag and add a few drops of tea-tree oil as a natural antibacterial to reduce stink.

In our experience, merino and other wools almost never get smelly even after ten days on trail… unless you wear a synthetic base layer underneath them, when something horrible happens after only 2-3 days. Once home, generously spray stinky areas of wool base layers with methylated spirits (denatured alcohol) to open the fibre, and let them sit for 15 minutes before washing as normal. Hanging them inside out in direct sunlight helps remove any residual odour.

I unfailingly use laundry wash bags at home for all our merino clothing and, on long thru-hikes, even pack a few into bounce boxes because track town laundromat top loaders are notoriously harsh on clothes.

Most of our merino tees have retained their shape perfectly even after years of cold (front-loader) machine washing almost weekly in ordinary enzyme-free liquid laundry detergent, not wool wash.

After one interstate hike, I washed several tees, including the green Ottie pictured, in a laundromat and realised only when steam was rising from the machine that I’d used the wrong setting. The water was so hot I couldn’t even submerge my hand to remove the clothes, so I ran to fetch a wooden spoon from our car camping kit to fish everything out. A few of the synthetic clothes survived but the same could not be said for our merino socks and several Macpac and Icebreaker pure merino tees. However, we were astonished that our Ottie tees were perfectly wearable, losing almost no length and becoming only marginally more fitted: hardly different from new! More recent Icebreaker base layers have a little elastane added, so may perform better.

Sustainability and Environmental Impacts

Because polyester and nylon are made from petrochemicals, they are not biodegradable. However, nowadays you can find polyester clothing made from recycled plastic PET (Polyethylene Terephthalate) bottles, which are 100% recyclable. Polyester clothing from recycled materials uses about half the energy to produce, so is more sustainable.

However, polyester and nylon clothing are a source of microplastics – more correctly, microfibres – in the environment, especially (but not only) the marine environment, where they disrupt growth, reproduction and disease-resistance in micro- and macro-fauna, as well as impacting human health, though precise effects are still being studied. Every time you wash your polyester or nylon clothing, microplastics are released into the environment.

If you want to reduce the amount of microplastics you send into sewage, this article suggests that you launder less frequently, in cold water using liquid rather than powder laundry detergent, with less detergent, with a full load in a front-loading machine. Dry clothes on a line rather than tumble drying.

You can also invest in laundry balls and laundry bags to reduce microfibres released by 20%-33%.

External filters fitted to washing machines are far more effective, catching up to 90% of microfibres. Many countries are in the process of mandating these filters in washing machines but, until then, aftermarket options in Australia include Planetcare and Samsung, although the fibres still end up in landfill.

The Bluesign system rates fabrics and clothing products that have high standards of sustainability, environmental and worker safety.

Australian merino is harvested from sheep that, depending on individual farming practices, contribute to land degradation; for animal-welfare afficionados, mulesing-free wool base layers are hard to find (in Australia, they rely on certain breeds of sheep; in our opinion, in other breeds fly strike is more harmful to the animals). Ottie Merino is certified mulesing-free. Look also for tRWS (Responsible Wool Standard) certified clothing.

Some alpaca and yak wool products are produced by small-scale local cottage companies that purport to support their local communities; after due diligence you may be happy to pay the extra.

For those searching for sustainable animal-based fibres, New Zealand possum down is a theoretical but limited possibility for hiking. Possums are environmental pests in New Zealand, so harvesting them benefits the native flora and fauna there. With its hollow fibres, possum fur is warmer, softer and lighter than merino (quoted amounts as to what extent vary wildly) but, in our experience, not sufficiently durable for bush-bashing or hard-wearing clothing like hiking socks and gloves. Of course, all merino-possum blend clothing is also extremely expensive, and we have been unable to find any base layers incorporating possum fur; if you know of any, please share in the comments.

Reader Kerry Forrest at Frenchman’s Cap in favourite hiking clothes. Kerry says, “My advice is to find what is comfortable and works - then stick with it. I keep my walking clothes until they wear out or are so thin or holey that they can't be worn (or trusted). In fact, I've replaced my boots more often than my outfits. I prefer to walk in shorts with gaiters and a merino t-shirt, adding and removing layers as needed.” (Image Credit: Kerry Forrest).

Take a moment to think about the features (price, stink-resistance, durability, warmth to weight ratio, drying time/water absorption, sustainability) of polyester, nylon, wools, silk and semi-synthetics. What characteristics are most important to you? In what weather do you hike most often? What will you look for on a label or under ‘specifications’ online when next you assess a potential base layer purchase?

Base layer Design Considerations

Thermal base layers

Form-fitting or loose (tees, shirts, polos, sun hoodies, activewear)

Activewear/Mesh and other weaves and knits

Sun Smart Features

Colour

Torso Length, Droptail

Offset seams

Panels (shoulder, modesty)

Thumb loops

Hiking pants/leggings/shortsd/zipoffs

Thermal Base Layers

Geoff wearing a synthetic thermal base layer, me wearing a long-sleeved merino thermal base layer over a short-sleeved merino tee.

If you’re choosing thermal base layers (to add warmth, as opposed to hiking tees or shirts), 260gsm merino is great for layering in camp, as sleepwear in cold conditions, and even as a mid-layer but is, in our opinion, a little warm for hiking in most Australian climates. Very light and cheap merino thermals such as Aldi’s 150gsm ones are ideal for layering in Australia’s warm seasons and climates but aren’t really enough for all but hot-blooded folk when stationary in camp or as sleepwear in cold conditions. Midweight thermals around 200gsm are, in our opinion, the most versatile, though of course it depends on whether you are a cold fish or not, where you hike and how actively you hike. Some hikers wear merino thermal long johns or hiking tights under shorts during the day.

Plus-Sized XTM merino thermal Baselayer top and bottoms XL-7XL in men’s and women’s.

Image Credit: Plus Outdoor

On longer hikes, Geoff and I usually each carry two merino base layer tops: a standard short-sleeved one for hiking, plus a lightweight or midweight long-sleeved one that we use for sleeping, as a second layer in camp, or as a dry top to change into if our short-sleeved tee is wet. The long-sleeved top and long johns are always kept dry so we don’t use them in heavy rain, but we sometimes add them over our short-sleeved tee under a fleece, or under pants in cold weather when we’re moving slowly.

If you’re on a budget, get polypropylene thermal base layers.

When choosing thermals, consider

where you most often hike,

how active you will be ie will you work up a sweat (it’s easy to become chilled when moving slowly in technical terrain)

how you will most likely use your thermals (hiking?sleepwear?in camp?) and

whether you are a cold fish or toaster.

Other form-fitting Base Layers

Many hikers prefer form-fitting base layers like tees that require a degree of wicking for temperature management; thermal base layers are always fitted. Form-fitting base layers shouldn’t be baggy because you want the fabric against your skin to most effectively wick, but a very tight base layer is uncomfortable for multiday hiking.

As we’ve seen, polyester is usually (but not always, depending on knit or weave) preferable to pure nylon; look for odour, moisture and insect treatments (or use a wash-in permethrin if hiking extensively in tick country, see below).

Polos are an alternative that offer the added protection of a collar, and often a slightly less fitted but more stylish appearance than a tee.

Activewear Base Layers/Mixed Panels and Materials

Activewear base layers such as those by Brynje may be wool or synthetic but are distinguished by their knit, which is open to varying degrees and sizes. As mentioned earlier, their UV protection is minimal, so not great for hiking in Oz unless in our alpine/montane winters, which is after all the kind of climate for which they are designed. Devold sells base layers with mesh panels. Both brands are extremely expensive in Australia: wait for sales. Airmesh is a lightweight nylon-elastane blend but, as seen earlier, much cheaper ones including plus sized are available at chain stores like KMart, Target and Big W.

These base layers often include different numbers of panels in different weaves, knits and/or materials in one garment. When looking at your base layer, consider why the panel is there, and whether it is functional or only cosmetic; you’ll find ‘modesty panels’ in the chest area of women’s mesh garments, whereas panels in the crotch are for every sex’s comfort.

This Brynje women’s Wool Thermal Light has a modesty panel but, for multiday hiking, the lack of shoulder reinforcing is problematic. (Image Credit: Brynje)

This Brynje Wool Thermal Shirt is much better for multiday hiking, though worn on its own under a pack without an insulation or shell we wonder as to its durability. (Image credit: Brynje)

Other functional panels include those that are:

More durable than the rest of the garment, usually in places vulnerable to abrasion or wear such as knees, butt, elbows and the tops of shoulders and upper back.

Warmer, usually around the torso

More breathable, often at chest, back and underarm areas (the effectiveness of tiny underarm areas is debatable in overall heat regulation, but they might be a little less stinky or damp).

Stretchier, usually at knees and elbows

Read labels carefully and consider the materials and knits/weaves to determine whether the differences are substantive.

Hiking Shirts

Subscriber Yvonne E writes, “On the Travers Sabine, I took my favourite, trusty blue hiking shirt. I’m prone to sunburn, and this shirt has a collar, short sleeves that aren’t too short, and I can button it up to protect the neck area. As a hot hiker, the fabric is perfect: cool, lightweight, not plastic-y, not (too) smelly, and dries super fast. This shirt has been everywhere, and never let me down.” (Image Credit: Yvonne E.)

A base layer can also be in the form of a collared, long-sleeved button-up hiking shirt. Usually synthetic – polyester in a knit or weave, polyester-nylon blends, or sometimes cotton-polyester blends for reliably hot climates (avoid pure cotton/flannel) – they can be as effective as wicking base layers at keeping you dry, and can be more so in hot climates. They are not skin tight: instead, the looser fit provides excellent ventilation allowing sweat to evaporate, rather than wicking from your skin. Of course, the material itself must breathe well too, and wick in the areas held close to the skin. Because hiking shirts are usually not stretchy, their SPF is less likely to vary over different parts of the body than that of stretchy sun hoodies.

Many hikers prefer hiking shirts because they are more stylish and versatile than thermal base layers. Long-sleeved hiking shirts are particularly versatile: sleeves down for sun protection, or roll them up for a short-sleeved shirt; look for sleeve-keeper tabs. Other hikers appreciate chest pockets: softer wool or synthetic knits usually lack sufficient form to support a pocket that can carry anything without deforming.

Our friends Patrick and Helen wearing their trusty hiking shirts at the end of the long distance Bibbulmun Track. Pat is carrying his phone in his shirt pocket.

Depending on weave, hiking shirts can be quite wind resistant and, in colder weather, you can wear a wicking base layer under them. The looser fit also provides better insect protection than form-fitting thermals: as a mosquito magnet, I’ve been bitten through 260gsm wicking baselayers, but not shirts. Some synthetic hiking shirts are factory treated with permethrin, ideal for tick country.

Quality hiking shirts often include a vented panel across the shoulders and mesh panels under the arms but, when wearing a pack, the effectiveness of the former is debatable, and the size of the underarm vents is again usually too small to be significant unless you’re someone who sweats buckets.

You can find hiking shirts in outdoor shops, but any synthetic shirt of appropriate design is fine, even retired polyester business shirts that you’ve liked wearing in the office! In Australia, you sometimes find excellent hiking shirts at tradie shops, but check the label because most are cotton or cotton blends. Many have collars with an extra tab that adds cover when you wear them turned up.

Sun Hoodies

Sun hoodies on Tasmania’s buttongrass and low heath (Image Credit: Cameron Semple).

Sun hoodies are a relatively recent base layer development for those who don’t want to slather their arms and neck in sunscreen every four hours, or wear a long-sleeved hiking shirt/conventional base layer. Ideally, they are lightweight with some stretch, highly breathable, comfortable against the skin, cool, and pale in colour. They need to be somewhat form fitting but not tight to allow for both evaporative and wicking cooling. They are designed to be worn with a peaked cap, but you will likely still need to apply sun screen to the lower half of your face.

Before sun hoodies, hikers just wore the aforementioned collared shirts or long-sleeved tops with a legionnaires hat to the same effect, so no need to replace what you’ve already got: hoodies are currently fashionable, but not necessarily better.

The 135gsm Mirage Merino hoody (Image Credit: Zpacks)

Sun hoodies are available in merino or synthetic fibres, so remember the differences between nylon, polyester, merino and lyocell when choosing one: many are nylon/spandex which breathes less well than polyester in the kind of tight weaves required to block UV rays.

Always check the SPF. Although some articles suggest there’s not much difference in the amount of rays various SPFs block, this is a misunderstanding of how SPF works. The Skin Cancer Foundation explains:

“The SPF number tells you how long the sun’s UV radiation would take to redden your skin when [wearing the product] versus the amount of time without [it]. So ideally, with SPF 30 it would take you 30 times longer to burn than if you weren’t wearing [it].

“An SPF 30 allows about 3 percent of UVB rays to hit your skin. An SPF of 50 allows about 2 percent of those rays through. That may seem like a small difference until you realize that the SPF 30 is allowing 50 percent more UV radiation onto your skin.”

The OR Echo Hoody has an SPF of just 15, and you can tell it’s insufficient because even in the promotional image you can see the model’s bra through the fabric. (Image Credit: Outdoor Research)

Prana Sol Shade with a 50+ rating: a much more sensible option for Australia although it will allow less air flow through. (Image Credit: Prana)

Some, such as the nylon OR Astroman Air indicate a range, eg 30-50% SPF which is a significant difference and not particularly useful; others such as the polyester Prana Sol provide a minimum rating eg 50+, which is much more helpful (and a far better rating).

The 135gsm (3.98 oz/sqyd) Mirage merino hoody with a tight knit and reportedly zero transparency is very light and at 16.7μm would certainly be very comfortable against the skin. However, there are reports of hikers burning through it on the upper shoulders, and this would be possible, even likely, if the material is being stretched by a pack whilst worn, or thinning after extended use. We’d also be a little suspicious of such a light material’s durability when worn under a medium to heavy pack.

Here is a clever but eye-wateringly expensive 30+SPF polyester design that blends hoody and button down shirt although the website doesn’t provide fabric weight. (Image Credit Anetik).

Check also for those thumb loops – those that cover the backs of your hands are better than those tops that only reach your wrist.

However, if you think you’d prefer a hoody to your current system, spend time comparing features before buying. Here are two comparative reviews:

Other Sun Smart Features

Hiking shirts and polos provide neck protection, as do long-sleeved tops to arms. Many women’s hiking tops feature highly impractical deeply scooped rather than crew necklines, and tiny cap sleeves: both are murder in Australia’s sunshine. Look instead for brands that expose less skin; men’s tees usually have longer sleeves and a crew neckline. Very light weaves and knits, including mesh, provide little sun protection: if your gaze sees through them, so can UV rays.

We have used sun sleeves with base layer tees to excellent effect in hot weather hikes; they too can be combined with other layers in cooler weather.

Colour

Dark colours dry faster when – and only when – hung in the sun, but are hotter to wear in the sun too; as we’ve seen, sun hoodies of any material should be as pale as possible in colour, whilst still blocking UV light.

Although certain colours are meant to attract or repel certain insects – mosquitoes are reportedly attracted to dark colours, ticks to light, flower pollinators to yellow, for example – I was unable to find any reputable studies other than conflicting ones (eg here and here) – to support the former two theories, though anecdotes abound (happy to edit in response to reputable studies, please send links).

Certainly, you see ticks more easily on light-coloured clothing but, in our opinion, your best bet if travelling into tick country is to regularly apply repellent to skin, and/or treat your clothing with permethrin which continues to repel insects and ticks through multiple wash cycles. If you’re someone who dislikes using chemicals, remember that ticks carry the debilitating lyme disease overseas, and can also cause a permanent allergy to meat protein, including in Australia.

Weigh these potential harms against that of treating clothing with permethrin, which is poorly absorbed through the skin and which has a long history of use worldwide.

Torso Length and Droptail

Whichever hiking base layer top you prefer for multiday back packing, choose one that is long enough to extend well below the hip belt of your pack. Ones that are too short become untucked – usually at the back – with movement, and then the hip belt rubs against your skin with every step.

Geoff’s tee has plenty of length to sit well below the hip belt of his pack.

Tall women are particularly disadvantaged but, again, Ottie women’s tops, designed after extensive consultation with female hikers, are plenty long; alternatively in different brands, choose men’s models that are longer in the torso, or look to German or Scandinavian brands that cater to taller folk.

Droptails designs that are a little longer at the back than the front are common and helpful in many hiking tops.

Flat Seams, Offset Seams

A flat seam is sewn so that it lies flat in the same plane as the pieces it is joining, without the free flap produced with a plain or double-stitched seam. Look for them especially in any bottom base layers around the waist and hip area where a tight pack belt has the potential to cause a world of pain when there is any raised or thickened material between it and your skin.

Offset seams are those that are moved from the most prominent convex parts of the body contour – particularly load-bearing areas like the tops of shoulders, hip bones – where pack straps going over them are most likely to abrade, to places that are less likely to abrade. The most common offset seams you’ll see are at the back and front of the shoulder replacing one at the top, and a panel extending down the flank with seams in front of and behind the hip bone, rather than one directly over it. Bony people, seek out offset seams!

Thumb loops

These are great not only for warmth but also sun protection on the back of your hands: every sun hoody should have them, and any long-sleeved fitted base layer benefits too. Some cheaper models don’t incorporate the loop as a hole in the sleeve, but include a strip of grosgrain or similar sewn inside the sleeve. If your base layer lacks thumb loops, consider sun gloves or hand covers .

Pants, Shorts, Leggings and Thermal Bottoms

Zip off pants zipped off on a mild, leech-free day on the South Coast track.

Although most of this article focuses on upper body base layers, we don’t hike without bottoms! All the same principles apply, with a few extra provisos worth considering.

Consider zip-off pants for hikes with a wide weather window, for in camp, and for protection from cold and insects/leeches, but ensure the zip itself is well-covered, especially if you have hairy legs.

Wear shorts, skorts, skirts, hiking leggings or pants; wear thermals underneath or, for the bold or in heavier knits, instead of pants!

With our snakes in Australia, long loose pants with thick socks are more protective than are tight leggings, unless the latter are worn with gaiters.

Synthetic leggings worn under shorts and merino leggings worn under a hiking skort: mix and match as you wish!

(Image Credit: Kerry Forrest).

Pants with reinforcing panels at bum, knees and inner calves where boot and gaiter hooks catch or spread mud are much more durable. Look for flat seams at the waist so they’re comfortable under pack belts. Choose ones with slim, flat, light belts or elasticised waists.

Look for reinforcing at bum and knees of hiking leggings too. If you can find Fjallraven Abisko hiking leggings on sale, they last forever.

Tight synthetic leggings work for some but not all people with vulvas: funky time is real and not wonderful on multiday hikes!

I live in these Polartec Powerdry leggings (also bootleg style) at home and have multiple pairs, usually bought when on sale because they’re expensive at full price.

I’ve lost weight since buying them so they don’t fit quite as nicely as they used to, but fortunately quality fleece base layers like this survive multiple washes without losing their shape or stretch. In my opinion they are a little too warm and funky for multiday hiking in all but winter in alpine areas of Australia, but are ideal for cool, easy day hikes.

Although we’ve used many examples of different expensive hiking brands, you can find the same materials — and often similar designs — much cheaper in chain stores like Aldi, Kmart and Big W. Second-hand and Op shops are great for bargains now that you know what you’re looking for and at: get into the habit of reading those labels and assessing those designs to see whether the items meet your specific hiking needs.

Last but not least, if your current clothing does everything you need it to, wear it until it wears out!