Larapinta Trail Planning and Tips

All the slower hiking principles in these blogs are transferable to other multiday hikes. Learn how to tailor this exceptional walk to your exact preferences, with plenty of practical tips!

Throughout this extraordinary hike, you walk a series of parallel mountain ranges, following their spines before crossing through gaps and gorges, then traversing plains to reach another range.

The Grade 3-5 Larapinta Trail in the West MacDonnell Ranges is a spectacularly unique 230km/143mi (251km/156mi with side trails) through-hike in Central Australia. If you’re an overseas reader looking at the Australian map, zero in on the centre of our island continent, and that is where you’ll be!

Australian hikes span idyllic tropical islands in the north to Tasmania’s rugged central plateau wilderness, but the Larapinta is considered by many to be THE iconic Australian trail. Read on for everything you need for planning your own Leisurely Larapinta. We cover: [jump to]

Track Overview (terrain, track condition, water crossings)

Safety (emergency comms, managing heat, hydration)

FAQs (huts, campsites, non-freestanding tents, tent stakes, footwear, gaiters, insects, etc)

Our Part Two Slower Itinerary has everything you need (eg distance tables, downloadable spreadsheet, different daily option suggestions) to create your own Leisurely Larapinta Itinerary. And Daily Blogs comprise daily descriptions with lots of track photos so you can see whether this hike is for you!

Track Overview

The Larapinta is in Australia’s red heart.

Here’s the elevation profile - 7845m (25,740ft) elevation gain if you do the side trips - 7490m (24,570ft) without. Without side trips it’s approximately 230km (143miles) or, with our suggested side trips, 251 km (156mi).

There are 27 designated campsites. We used most of the main ones but not all of them, along with three wild camp locations, as well as official alternate campsites. Since we hiked, wild camp locations can now only be used in emergencies, such as managing heat or exhaustion, or presumably if nearby designated campsites are dangerously exposed. Official Park Maps divide the Trail into Sections 1-12 East to West, and we reference them throughout our blog in reverse as we are hiking W2E.

Drag apart to enlarge on a phone or, on a computer click on the map to enlarge, right click then magnify to drag across the route to see in more detail. We have larger images in the Itinerary blog, this is just a quick overview to illustrate how the trail follows the landforms.

You might imagine that because the West MacDonnell Ranges are in an arid environment, you’ll be traversing a vast expanse of desert, such as that which surrounds another famous central Australian icon, Uluru. But the West MacDonnells are a series of east-west running ranges and the trail is rarely flat and always varied, with marvellous new views and terrain every day.

Even more surprisingly, you’ll encounter water nearly every day too, whether it be wide rivers such as the Finke, tiny soaks with flocks of beeping finches, or icy pools in the gorges, cooled by the deep shade of red rock and lit by sun for only an hour or two at midday. The Larapinta not only links every one of the famous landmarks – Redbank, Ormiston, Hugh and Serpentine Gorges, Standley Chasm, Simpsons Gap, Ellery Creek, Birthday Waterhole and the Finke River – but also climbs the highest peaks.

A fun wade and swim in Hugh Gorge on a cold and misty day: brrrrr!

The awe-inspiring nature of this landscape is difficult to convey; even pictures don’t do it justice. Nearly everyone we talked to mentioned the almost palpable impression of the aeons, and of course the Traditional Owners, the Arrernte, have their own long history and dreaming stories: take one of the guided tours at Standley Chasm. The land is eroded and smoothed by millennia of ancient seas, baking sun and flooding rain; geologists we met were ecstatic about the stories they read in the rocks, although one mystery, the formation of the Ranges themselves in the centre of our country, has never been explained, at least by Western science: it’s simply referenced as ‘an event’.

Geology writ large in Serpentine Gorge

Botanists read another history of plants adapting in the most amazing ways to the extreme environment: even a fern survives on baking rocky hillsides! Twitchers will marvel at the flocks of budgies as they whoosh by like a squadron of tiny fighter jets.

After rain at any time of year, wildflowers sweep across the landscape. Here, Hairy Mulla Mulla (Ptilotus helipteroides).

The Larapinta is demanding by Australian mainland standards. The trail is rocky and rugged, with some sections requiring scrambling: you’ll need care but not technical expertise. Many of the beautiful gorges are bouldery; climbs and descents are often steep without switchbacks. Subscribe to see the daily blogs for lots of images of the track each day so you can judge whether it is for you or, as most of the guided tours do, select which highlight sections are within your ability!

A steep scrambly section. These are less daunting than they look because you pick a route of natural steps down the face.

The bouldery sections through gorges and narrow valleys are often slow going too.

You have water crossings through creeks and gorges, though the number depends upon recent rainfall:

Wading through Davenport Creek: levels and flow rates are much higher after rain but are easy now.

Heat, even in midwinter, also impacts hikers because some sections have little or no shade:

Although much of your hike is through gorges and along ridges, the Larapinta includes plains without shade.

But you also experience Australia’s vast sky and wide horizons from numerous high points, often at dawn or dusk. Mt Sonder, Brinkley Bluff, Count’s Point, the High Route and Razorback Ridge offer unparallelled views in every direction and the landscape is utterly unlike anywhere else on earth. It is an unforgettable hike that gifts a lifetime of memories.

Vast views on the Alternate High Route in Section 4

Click here to start walking with us (coming soon) or read on for whole of track hike planning information and advice.

Is the Track for Slower Hikers?

Answer: A Definite Yes!

Most people hike the twelve sections of the Larapinta Trail over 14-18 days, including one rest Day at Standley Chasm. The Northern Territory Parks Service recommends you allow twenty days for the full end-to-end hike. Trail runners complete the distance in just one week, but we took a glorious 23 days, including four rest days.

This time may seem excessive, but we met many hikers who were genuinely envious of our itinerary. Many had underestimated the impacts of heat and the ruggedness of the trail. One young couple – both tour guides – having a day walk on their day off, told us they wished that more people took their time on the hike: they had seen firsthand too many who, rather than conquering the trail, lost the battle and who bailed at the first extraction point, usually Standley Chasm.

Of course, not everyone has the luxury of time, but this is a once-in-a-lifetime experience. If you’re a leisurely hiker considering the Larapinta, or hiking with children, carve out the necessary days rather than trying to make the hike fit your holiday, or you will be disappointed.

Our relaxed suggested itinerary utilises all the tricks – extra rest days, intermediate campsites, early starts, contingency days and more to ensure that your Leisurely Larapinta is enjoyable. Our slowerhiking itinerary describes our recommendations in detail, with distance tables and other resources to help you tweak the hike exactly to your requirements should you prefer to walk slightly faster or slower. Read the logistics below first, then study the itinerary.

A cup of tea and a relaxing lunch on a rest day in splendid seclusion on the banks of Ellery Creek North, far away from the bus groups at Ellery Creek South.

How to Get There

By car (a few days) or plane from any capital city to Alice Springs. The luxurious Ghan is a world-famous train from Adelaide to Darwin; it passes through Alice Springs. Only choose this if you are a train enthusiast because it is by far the most expensive option.

Once in Alice Springs, you’ll need a track transfer to Redbank Gorge if hiking west to east (W2E) as we recommend, or a pickup from Redbank if hiking E2W. These transfers are expensive but, even if you have a car, parking it at Redbank Gorge for three weeks isn’t ideal. We left our car in secure storage, an open air facility at Self Storage Australia in Alice Springs. Other hikers used the airport, but be aware that the airport is not open 24 hours so check when you can park your car there, and also the availability of taxis. Without a car, you also need a transfer company for your food drops. We heard mixed reports on the trail about different track transfer companies. Do your research because, at the time of our hike through to time of writing, some companies are more reliable than others.

First two nights at Redbank Gorge

When to Hike

May-August are the most popular months, and starting in mid-June ensures that slower hikers won’t be hiking into heat; Geoff checked temperature and rainfall records and determined this was the best time for us, with cooler temperatures the most important decider. Consider delaying your hike if a heatwave is forecast, stay put in camp, or hike before dawn or in the early morning with a long siesta in the middle of the day. Faster hikers can start later in the day or year. Add contingency days to your itinerary in case of delays. Hiking in summer is strongly discouraged: it is simply too dangerously hot. Heavy rainfall just before your hike may significantly change terrain as floods rise quickly. Plan also for cold if hiking in winter.

Bookings: Parks Pass, Trail Pass and Campsites

Book online. Numbers on trail are not capped but track transfers are less flexible at short notice so it pays to book early to ensure you get the transfers you want. We booked sites we thought we would stay at, but weren’t worried if our itinerary changed and we ended up elsewhere instead. In all, there are 27 designated campsites, but some are more basic than others. Campsites like Hilltop, Mt Giles Lookout, Waterfall Gorge, Ghost Gum Flat, Fringe Lily Creek, Brinkley Bluff and Millers Flat can be booked but have no facilities and are just locations where Parks encourage people not staying in formal campsites to stop. These sites are particularly relevant to slower hikers who may not make the standard distances between formal campsites. You can now only stop at designated campsites, unless in an emergency, or we assume if necessary to manage your safety or wellbeing: wild camping is always preferable to an emergency evacuation from the track!

This wild campsite was marked on Alltrails. We walked 4.5 km past a formal campsite (Rocky Gully) and stayed here instead to shorten the following day, which was forecast to be very hot.

You’ll need to book Standley Chasm separately. And if you think you will need a rest day, you can book multiple nights for campsites, as we did for Redbank Gorge, Ormiston Gorge and Ellery Creek North. Don’t stress too much if, once on trail, your itinerary changes a bit: none of the tent sites are allocated – it’s a first come, first served system and the folk at Standley Chasm understand that logistics or injury may mean you arrive a day or two early or late and will honour your bookings (we also booked two nights at Standley Chasm for a rest day there). So, if you are part way through your hike and need to stay an extra night at a campsite, that is no problem.

The logistical costs we directly incurred as part of completing the hike in mid 2024 were as follows:

If you live outside of the Northern Territory, you need a parks pass (AUD60 for 12 months per person) (AUD120 for us).

There is a trail fee which is automatically added to your campsite fees; at time of writing, it is capped at AUD125 for 5+ nights. (AUD250 for us).

Then there are your parks camp fees (AUD10 per person per night). (AUD420 for us).

Camping fees at Standley Chasm (AUD25.50 per person for first night AUD15 per person the second) plus a AUD5 fee to use a storage room for resupplies. (AUD86 for us).

An AUD10 storage room key fee with a AUD50 refundable security deposit.

Transfer fee to Redbank Gorge to the start of our hike AUD225 per person. (AUD450 for us).

All up direct costs for a 23 day itinerary: AUD1336 for two or AUD668 per person, or AUD29 per day. Faster hikers will spend less.

We did our own food drops so, if you don’t do that, then there are additional costs associated with those. Several companies offer these services so you’ll need to check to see which one suits your requirements best. The cost is typically around AUD85 to AUD100 per box per site and they give you a box to fill, collect it from you and place it at the food drop location for you. Whilst they collect the box and dispose of any rubbish post hike, if you want to retrieve anything you leave in the box (eg spent camera batteries, extra gear you decide you don’t need to carry, clothes you’ve changed etc) then an additional fee is usually charged (between AUD50 and AUD80). So you might be looking at an additional AUD400 or more for food drops and retrieves.

Hiking the Larapinta is not cheap.

Maps and Resources

Buy a hard copy waterproof set of the official maps .

Digital maps include Avenza (free) and Farout. However, note that the Alltrails map shows the route going through Ellery Creek South rather than the official (and, in our opinion, greatly preferable) Ellery Creek North.

Facebook Larapinta Trail group. This is handy if you want to coordinate food drops with a car owner, or for specific questions of a timely nature.

John Chapman’s excellent Larapinta Trail is invaluable for planning and we highly recommend you buy it. John’s books are famous, but he is not your average mortal: slower hikers should disregard his time estimates! You will take much, much longer. Even average hikers often take longer!

Resupply along the Trail

Dropping our resupply box at Serpentine Gorge

The locked storage facilities are at Ormiston Gorge, Ellery Creek South or Serpentine Gorge, plus a storage room at Standley Chasm. If hiking W2E and staying at Ellery Creek North as we recommend, drop at Serpentine Gorge instead of Ellery Creek South.

When you arrive in Alice Springs, collect your key for the resupply storages from the Visitor Centre; you receive your deposit back when you return the key; the Standley Chasm storage has a small fee that you pay with your separate booking.

Slower hikers should utilise all three resupply options. This reduces your daily pack weight, which is important as we’re carrying more days of food. If you have your own car, do your food drops one or even two days before your hike (400km will take the better part of the day). If dropping off your own resupplies like this, you’ll need another trip to pick up your boxes after your hike, a total of about 800km.

As mentioned earlier, track Support Companies do food drops in conjunction with hiker drop offs or pickups. You’ll need either a drop off (W2E, recommended) or pick up (E2W) yourself from Redbank Gorge, too, and this will usually be with the same company who does your resupply drops. Some offer a small discount for multiple bookings.

55 litre resupply boxes are the norm. We used smaller ones because that was what we had at hand. Check with your resupply company if you are using one.

Our resupply box packed with luxuries at Ormiston: deodorant for the hot shower and laundry detergent for washing here, fuel, powerpack, lightweight dehydrated meals and snacks, as well as maps for the next section and medication. Many hikers also pack wine… I told Geoff we should have brought a bigger box!

The free food hiker box, absolutely chockers with good stuff, at Standley Chasm. There’s also a box with gas canisters.

You’ll need to fill your box because none of these locations have shops with the kinds of supplies you need, though you may find a good selection in the discard box at Standley Chasm where bailing hikers leave excess food. See our post on resupply and food drops for thru-hiking for more tips on food and resupplying. The Larapinta is an excellent stepping stone to longer thru-hikes, because many of the same logistics apply.

Slower hikers should ideally carry one extra day of food between each resupply for maximum flexibility.

Electronics

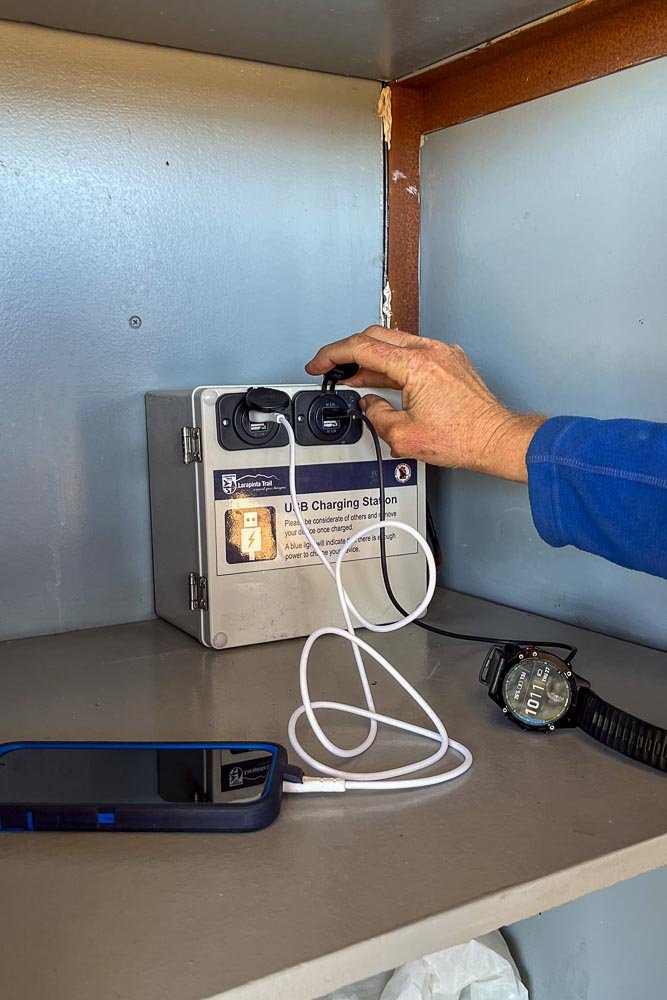

The Larapinta is in one of the few environments in Australia where a portable solar panel makes sense. However, with (somewhat unreliable) USB charging points at the huts, it’s a lot of weight to carry unless you use a LOT of charge.

Unfortunately, with only limited battery storage, the hut chargers only work when the sun is high and charging slows to a trickle when multiple devices are plugged in and at the end of the day. Worse, some devices misread the charger and actually discharge power when sunlight is insufficient, so check your devices regularly, especially at first, to ensure the charge is actually increasing. Take advantage of hut chargers on your rest days: others are unlikely to be using them in the middle of the day.

Chargers are inside the cupboard in the huts. Hikers finishing at Redbank Gorge have left half full and full canisters as well as bug repellant, alcohol fuel and miscellany. The wine bottle, sadly, was empty.

Charging at midday at Ellery Creek North. It’s working with two devices, but we found that one device at a time worked better.

At Ormiston and Standley Chasm, charge your devices at the café verandah/amphitheatre and in the camp kitchen/outdoor camp area respectively. Standley Chasm also has charging facilities inside the cafe above the fireplace. Pop a bungee, cord or elastic and a double adaptor into your resupply boxes (if you are also picking them up) to take advantage of in-demand wall sockets.

The main chargers at Ormiston Gorge under the verandah. A double adaptor in your resupply box is helpful!

There’s another powerpoint high on a wall. We used a rubber band to secure our powerbank.

With the amount of photography we do, we also carried spare batteries and powerbanks, but popped them into our resupply boxes so we didn’t have to carry all of them all the way.

Safety

Emergency Communication

The rocks are hard and sharp and effortlessly destroyed my iphone camera lens. It could just as easily have been the screen (the screen protector cracked badly in the first week).

An Inreach or Zoleo holds power, is robust, and can be used to text family or download weather forecasts. A PLB is a bombproof emergency communicator with even better reception.

Please do not rely on your phone. Phone reception is scant, they are easily drained of power, and even the newer models with satellite reception are too fragile to be relied upon on this track. Carry a PLB or Inreach. A sprained or broken ankle in itself is not life-threatening, but if you are stuck somewhere offtrack or lost without comms unable to reach water, dehydration and hyperthermia kill quickly. Be aware that an Inreach is unlikely to get signal in narrow gorges. You can hire PLBs cheaply from Larapinta Trail Trek Support.

Manage the Heat : Hydration and Sun protection

Forecast temperatures are measured IN THE SHADE ie air temperature. It can be 12-15C HOTTER in the sun due to radiant heat. At temperatures above about 30C, it can be impossible to replenish water as fast as you are losing it when you are hiking with a pack in the sun. So a temperature of 35C can feel like 50C in full sun, which I think we can all agree is unsuitable for daytime hiking.

We started our hike in mid-June as hubby determined that was the coolest time of year: that was the most important limiting factor for me as an older hiker with less than stellar temperature regulation. It's common in older hikers for our temperature switches to become a bit glitchy; we sweat less, and get thirsty less than younger folk. Hubby and I stop for a good glug of water at least every hour, whether we feel thirsty or not. He sets an alarm on his watch on walks like the Larapinta.

Many of us older hikers are on diuretic medication which can exacerbate dehydration on hikes like this. I would be physically unable to hike at this time of year.

However, if you're not like me and are hiking just outside the coolest time of year, you have options to hike more safely if the heat spikes.

Choose to walk earlier in the morning, leaving while it's dark, or late afternoon into the night, with a siesta in the middle of the day. Night hiking doesn't work for Geoff and me on a rough trail like the Larapinta because of our eyesight; we'd just be swapping one risk for a different one.

If you know a hot day is coming, you can have a longer day before or after, and a shorter one on the day.

Or you can stay an extra day in camp and rest on the hot day (because you're carrying one extra day of food in each resupply).

It's now illegal to wild camp on the Larapinta so you should always *aim* to stay at designated campsites, and we recommend this but, if you are flagging, becoming dizzy or unsteady then stop where you need to and address your health: it is always better to stop safely at a wild campsite to recover than it is to be evacuated from a designated one.

Similarly, if you do the right thing and book all the sites you expect to stay at, there is no way that Parks will penalise you for altering your itinerary for safety reasons, not least because campsites are all unallocated. They would much rather you do this than need evacuation. When we booked at Standley, we told them our arrival date might vary by a day or two either side: it was a complete non-issue because they, like Parks, understand that, on a long hike, itineraries need to be flexible.

Build that flexibility into your itinerary, with an extra day or two at the end in case you take longer than expected.

Know the symptoms.

As older folk, one of us highly sensitive to heat, we wouldn’t consider hiking in anything over 30C on this trail. Even 27C felt hot.

Know the symptoms of heat exhaustion and heat stroke and what to do for either. Two groups were evacuated from the track while we were hiking, and deaths occur with depressing regularity.

Sun protection is essential. It is usually sunny and much of the trail has little shade. Wear a hat, long sleeved shirt, sunscreen or sun sleeves as Geoff successfully trialled for the first time on this hike; he needed only a narrow smear of sunscreen on the gap between his t-shirt sleeve and the sleeve. Light-coloured clothing is cooler.

This hike suits a hiking umbrella. We could have sold ours many times over to red and dripping hikers we encountered. A sun umbrella provides the best protection in the middle of the day when you need it most. It shades far more than does a hat – your entire upper body – and you can take off your hat while using them, which makes for a much cooler head. Even Geoff could do this with his chrome dome!

Geoff doesn’t need to wear a hat or sunscreen on his face or head!

Shading most of the upper body and shoulders. The difference when hiking with one of these umbrellas in comparison to hiking with a hat has to be felt to be believed.

Hiking umbrellas clip onto the shoulder straps of packs, so you can still use trekking poles. They are no good in wind or on overgrown trails, but they were one of the best decisions we made on this hike.

Hydration

Carry plenty of water: the air here is extremely dry. We carried 3L each on some days but were hiking shorter distances than most. If covering longer distances, you need more water; ditto in heat. You can easily drink 6L or more in extreme weather, one reason why summer hiking is strongly discouraged: when physically active in extreme heat, you cannot replenish your body’s water fast enough to keep up with loss, even should you be able to carry the many litres needed. On days with dry camps such as Hilltop, Hermit’s Hideaway and Brinkley Bluff, you need extra for the evening, night and following morning/day depending on the distance to the next supply.

Drink regularly. We older folk with rusty internal switches often don’t get as thirsty as young guns. Geoff and I drink every hour whether we feel thirsty or not.

Despite the name, Waterfall gully is usually dry but, if there is water, definitely treat any you collect because many hikers swim here.

There had been reports of illness so we treated tank water we might drink but didn’t separately treat water boiled to rehydrate meals. We usually don’t treat tank water if Geoff is confident of the water source: it is more important to observe good hygiene after using the toilets. Some people collect water from the tank on the opposite side of the hut to the toilet rather than the one closest to try and lessen the faecal-oral infection route potential. Always treat water collected from natural sources on the Larapinta. Use sterilisation tablets (Micropur) or a water filter. Steripens don’t work in cloudy water, which may be the case if you have to collect from sources between huts.

Navigation

The trail is, in our opinion, well-signposted but we encountered hikers who had missed turnoffs and had to backtrack. In open areas, the trail is generally easy to follow with regularly placed signage; close to Alice Springs one section is criss-crossed with cattle tracks but you should always be able to spot the next marker post.

You’re most likely to lose the track in the gorges, following the wrong branch or exiting up a kangaroo track as happened to one hiker who had to be rescued while we were on trail. It’s essential to be observant: signs can be on trees, posts, rocks or branches at, above or below eye level.

This marker is obvious but they are often more cryptic. Sometimes they’ve fallen off and been propped against the base of a tree. It’s easy to focus on your footing in these gorges and nothing else but, each time you come to a marker, pause and scan for the next one. If you can’t see it immediately, keep pausing to scan. You can also look behind you to spot markers going the opposite way. If there is no signage or marker to leave the gorge when you reach what looks to be a side track, then it is almost certainly not the right one.

Your best bet for accurate navigation is to read your map carefully the night before or in the morning before you start hiking. Although you’ll find overview maps in the huts, these are not enough to navigate by. Your topographic maps (paper or digital) give you a much better idea of what the day holds in store. For example: we will hike through the gorge for about a kilometre, passing a branch to the left halfway, then take the second left branch for another kilometre. The track then leaves the gorge on the east/right side and follows a spur for another 500m, before dropping down on the northern side to a plain where the track swings east again etc.” If you know your hiking speed, you can use times instead of distances. Using major land features, or handrails, contextualises the track so that you are much less likely to take a wrong turn.

Your digital map (Avenza, Farout, Alltrails) usually provides your exact location… but not always, especially in deep narrow gorges with poor GPS signal.

If you see a side spur or trail with rocks or branches laid across it, this is the universal sign that it is NOT the main route.

Leave No Trace

People who squat to pee, please shake dry, carry a Kula cloth, or use a travel bidet and towel instead of paper. If you must use paper for pee, put it in a double ziploc (pee is sterile) to empty at the next toilet. A bidet is good for poo, too! Please buy and carry a Deuce of Spades toilet trowel or equivalent.

Use the camp toilets wherever possible as you pass them but, if caught short, bury poo at least 15cm deep, well away from water. It is highly unlikely that you will be able to dig a 15cm hole at any of the high camps even with a toilet trowel, as the poo reportedly under every rock and the teeming flies bear witness. If you can, go before you ascend, or hold on until you reach softer ground. A poo tube or pot should really be required here and if we had known just how hard the ground is, we would have carried one.

Do not make new campsites unless in an emergency. Most of the possible wild camps have already been cleared, so utilise them only if you can’t reach a designated campsite, or conditions preclude their safe use.

Use no soaps or detergents in or near water. Wash dishes well away from streams.

A refreshing wash with a sponge and nothing else: definitely no soap, even so-called wilderness ones.

Buffel Grass. This scourge might look pretty but it is an environmental disaster of monumental proportions. When you finish your hike, check your shoes and tent for any seeds: you do not want to bring this horror to your local area.

Take a good look to see what is hidden in the crevices of your shoes.

All these seeds from just one shoe!

Other General Tips

Store your food securely, either in lockers or hung. At the time of year we hiked, small native critters weren’t an issue, but they can be in other seasons and they quickly learn to find food. Some of the huts have steel mesh storage boxes under the platform but check that the one you choose closes fully without gaps because many are bent out of shape. The cupboards in the huts also often don’t seal properly. We hung our food bags most nights. It may not be necessary but it’s one of those things that you don’t want to discover when it’s too late.

Underfloor food storage lockers.

Plan conservatively to allow for delays due heat, injury or exhaustion.

Add contingency days to the end of your trip to allow for delays on track.

Utilise the weather forecast on your Inreach

Be familiar with your gear

Carry a First Aid Kit

Start early to maximise daylight hours and beat the heat. Take a siesta in the middle of the day if it is hot.

Utilise intermediate campsites

Don’t hurry in tough terrain. The roughness and slipperiness of the gorges and the steep descents claim many victims who slip or wrench joints. Slow and steady wins!

Take it easy, especially when it’s wet

Keep your trekking poles handy, but don’t be afraid to stash them either: in some sections, your hands will be of more use.

Minimise your pack weight and avoid having things hanging off the outside: they will likely be lost. On some days, you are scrambling through rocky gullies. Your pack should be as light as possible, without skimping on necessary safety equipment, clothing, food and especially water. Like the Overland Track, the Larapinta attracts a lot of inexperienced hikers. We saw some gigantic packs with struggling hikers underneath them.

Left behind by some poor sod at the first camp out of Alice Springs. This hammer weighs more than our tent and (empty) pack combined, with countless rocks every step of the trail!

Pack the correct clothing, including waterproofs and warm layers like beanies and gloves (we had -6C atop Brinkley one night and early morning, with windchill dropping the apparent temperature to -11C). Carry an insulation layer (eg fleece) plus a rainshell.

Wiping ice from the inside of the tent; the outside was also crispy with ice. During the night my bare butt confirmed that it was every bit the -11C apparent temperature with windchill outside!

We also experienced extremely cold and wet weather on trail; a young trio we met wore drenched puffy jackets which had completely lost their insulating properties (they had no rain shells). The temperature was in the single digits and they had yet to swim Hugh Gorge: we were worried for them.

Also very cold and windy on Razorback Ridge. I was wearing every layer: short-sleeved wool thermal base, long-sleeved wool thermal base, fleece, puffy, rainshell, gloves, balaclava and beanie… and I was still cold in the places exposed to the 30kt+ winds. Unusually, Geoff was also wearing every layer except his puffy. Because much of the ridge is scrambly, we were moving too slowly to generate our own heat.

Ensure you are moderately fit.

Wear footwear with grippy soles.

FAQ

What are the Huts like?

Three-sided, well-designed and well-oriented. We slept in them occasionally, in our tent most of the time. In bad weather they are crowded and by the time we slower hikers arrive, all the spots are likely to be taken. Bring a tent.

What are the campsites like?

There’s a good range of sizes, although the ones at elevation are smaller. Regularly used ones are cleared of the worst rocks but if you must wild camp almost anywhere else it will be like setting up on rubble: don’t think you can set up on any spot when looking at the maps. See our daily blogs for pictures of the campsites every day, including wild campsites we passed, to get a good idea of the substrates should you need to stop. Avoid making new campsites.

Can I use a non-freestanding tent with trekking poles? What tent stakes should I bring? Should I bring a groundsheet?

We used a non-freestanding tent without issue, but it’s essential to understand and have practised anchoring techniques. The substrate is mostly either sand or impenetrable rock. Our titanium nails and mini groundhog tent stakes were scarcely used and we left them in our first resupply box, keeping just a few. Instead, we deployed extra line (attached to guyout points before leaving home) and modified deadman anchoring techniques using (plentiful) rocks.

Even with a freestanding tent, make sure you bring guylines and anchoring options for all tie outs: the elevated campsites are exposed and subject to extremely strong wind.

Add line extensions to your guyout points. Use a hitch around a small rock, then pile rocks on the length of the extension to hold it. The three beside the line will be plenty; it’s easier than piling rocks vertically, and easier to adjust for length and direction.

Hitch/slip loop at end of extension to go around your small deadman rock or stick.

Because the rocks are so sharp, you’ll likely need to replace your extension line. This is spectra, about as strong as you can get. The nylon sheath has failed but the spectra is still holding for now. We always carry extra line.

If you own a lightweight tent designed for the Northern Hemisphere’s soft-leaved plants and generally soft substrates, bring a groundsheet. The rocks on the Larapinta are incredibly hard and sharp; we had to replace lines where deadmen had cut through. We suspect that ultralight groundsheets such as Duck window film won’t be enough because we’ve had it tear on the much kinder bauxite gravel on the Bibbulmun. Tyvek is cheap and tough. We used it every time we set up the tent.

Rolling up the tent on the tyvek footprint.

The fine dust murders lightweight tent zippers. Although we’d cleaned ours before the trip, one jammed irretrievably partway through our hike. We taped the bottom shut so it wouldn’t split open any further. If yours is getting jammy, rinse it thoroughly with water at Ormiston or Standley Chasm.

What footwear is best?

There are as many answers to this question as there are shoes, but other than evening high-heels there are only two hard rules: grippy soles, and NOT brand-new shoes that you’ve never worn before. Open-toed hiking sandals are, in our opinion, unsuitable for most people because of the rocky terrain. Waterproof boots are unnecessary unless you prefer them. Shoes with a decent rand fare better and, because of the rockiness of the trail, some hikers might prefer shoes with a slightly more rigid rock plate.

We’ve seen numerous reports of people trashing shoes on the sharp rocks, but we suspect slower hikers are gentler on footwear than those in a hurry. My Topos Trailventure 2s and Geoff’s Hokas, neither known for longevity, were fine and not noticeably worn at the end of the track.

Should I wear gaiters and shorts or long pants?

If you’re hiking in the winter months, it’s unlikely you’ll see many or indeed any snakes – it’s warm, but still the cold season for them. Spiky spinifex is largely off the track. Many people hike in shorts with short or long gaiters but, as Australians accustomed to snakes, we both preferred a compromise of long light pants without gaiters. Other hikers wore leggings, bike shorts, running shorts, heavy pants, long and short gaiters, hiking skirts, you name it. Wear what feel most comfortable for you whilst providing sufficient protection from vegetation and sun.

Are insects a problem?

Not when we hiked but, at different times, flies and mosquitoes have been reported. We always pack bug nets (cheaper ones are available but these 11g ones are very light) to cover our faces/head. They are rarely used but we’re always happy we carried the extra 18g when we need them. A small amount of insect repellent is useful when sleeping in the huts. Prepare for flies and mosquitoes and you’ll have no issues.

Sitpads?

A chair is too heavy for most people on this hike, not least because you have a hut most nights but, with the exceptionally rocky terrain, this was one hike where we elected to bring lightweight 30g sitpads instead of our usual tyvek ones and were happy to have done so:

Sitpads and a sunset dinner from Hermit’s Hideaway.

Is the Trail for Inexperienced Hikers?

Not quite.

In our opinion, it shouldn’t be your first multiday hike but you certainly don’t need the same level of experience as for, say, the South Coast Track which is remote and without intermediate pick up points. However, setting out on this track without having carried your pack on steep and rocky terrain, with similar daily elevation gains and losses, or never having done an overnight camp with your kitchen, tent and sleep system, is a recipe for disaster and you are likely to bail at the first exit point because you are carrying too much, your gear doesn’t perform as expected, or you have miscalculated your ability to cover distance in heat.

Fortunately, this is easily remedied. Train with a full pack loaded with your gear before the hike. Search out local day hikes with similar distances and elevation gains and/or rockiness. Do a couple of overnight weekend trips to familiarise yourself with your gear, polish your navigation skills. Hike in warmer weather (25C-30C) to see how you manage heat and how much water you need, especially if you are older.

And tailor the hike to your ability using Slowerhiking’s Leisurely Larapinta Itinerary Framework

The Larapinta is deservedly Australia’s most famously iconic track through an ancient and spectacular landscape. Its deep gorges, red rock, unique flora and fauna, and vast views to horizons hundreds of kilometres distant are utterly unforgettable. Start Planning!

We respectfully acknowledge the Arrernte People as the traditional custodians of the land on which we walk and pay our respects to Elders past and present and to the Aboriginal people present today.