How to Stay Motivated on a Long Distance Hike Part One

Before You Start Hiking

Research, Motivation, Planning, Nutrition, Physical Prep, Itineraries, Chronic Conditions, Expectations, and Fears

Many people are mystified by the appeal of long-distance hikes. Walk, eat, sleep, repeat. Rain, heat, cold, exhaustion, discomfort. For months on end. Why on earth subject yourself to this? How do hikers finish? Why do they finish?

If you’re reading this, you’re probably already considering a long-distance hike, and you’re likely a leisurely hiker. Rest assured: the rewards are so much greater than you can imagine.

We made it… but of course we did! Interestingly, our mentor knew we would before we’d even started.

In Oceania, the trek might be the:

Bibbulmun Track in Western Australia (1000 km/620 mi)

Heysen Trail in South Australia (1,200 km/746 mi)

Australian Alps Walking Track (655 km/407 mi)

Australian Bicentennial trail (5,000 km/3,107 mi)

Tasmanian Trail (480 km/298 mi)

Te Araroa in New Zealand (3,308 km/2,055 mi)

In Europe, the

Grand Italian Trail (6,166 km/3,831 mi)

North to South Iceland Traverse (550 km/340 mi)

Via Alpina (2,600km/1,615 mi)

Via Dinarica in the Western Balkans (2,000km/1,054 mi)

as well as many more.

In the US, the

Appalachian Trail (3,525 km/2,190 mi)

Pacific Crest Trail (4,265km/2,650 mi)

Continental Divide Trail (4,873km/3,028 mi), as well as many shorter ones.

There are plenty of tricks, both physical and mental, to stay motivated on the track. Some of them can be done while you’re walking, but many of them start well before you begin your hike.

1. Research

Some gung-ho or easy-going folk simply decide to head off on a long-distance hike with little apparent preparation, planning or research, and succeed. However, they almost always have a degree of experience and/or knowledge already. Those with zero of either are less likely to last the distance because they’ll have inappropriate or insufficient clothing, food and shelter. They are usually carrying way too much. They lack insight.

However, you needn’t be an expert. Those with more hiking experience can succeed with little research and planning, those with little hiking experience can succeed with more research and planning. The fact you’re reading this gives you an excellent chance of success!

On the Bibbulmun, we met a couple who had never done an overnight hike before, let alone a long-distance one. One of them was aged over seventy, the other was in their fifties. They had researched extensively and planned carefully; they also learned on the track, and learned quickly. They weren’t exceptionally fit, and only one of them had trained, but they both completed their hike on schedule.

If you’re new to hiking, familiarise yourself with the early sections of the track by looking at maps, blogs and vlogs so that you’re less likely to miss turnoffs or be surprised by challenging terrain.

Checking the map

New hikers won’t be new when they finish a thru-hike. You’ll have seen different tent and cooking setups, sleep systems and packs, and food options. You’ll have tweaked your own gear and technique. Happily, no matter how experienced you become, others can always teach you more!

There are numerous blogs and websites about every thru-hike. Remember that in most cases you’re not bound by standard itineraries – see how you can adapt hikes to suit your own slower pace here and here.

Read gear and hiking reviews, and hiking discussion groups, especially those about your chosen thru-hike.

2. Understand Your Motivation

You’ve decided to hike the track. Why?

People trek for many reasons. Some are processing broken relationships, or repairing existing ones. Others are challenging themselves, or seeking self-improvement in fitness or mental health.

A rare conquering summit pic on the Acropolis, Tasmania, rather than our usual sitting with a view pic

When you’re motivated by physical challenge, rewards and gold stars are easy to define. Distances or kilometres per day, double-hutting and speed are simply measured, so faster hikers have concrete indicators of their progress. Hiking apps and gps watches are fun tools for such hikers. The destination is both the end of the journey and your motivation: a concrete goal. Most posts on social media are by people for whom such challenges – and often recognition of their achievement – are strong motivators.

However, leisurely hikers are likely to have different, less obvious motivations. A root cause analysis clarifies them.

Breakfast together in amazing places

Geoff and I have done plenty of hiking, and love being in nature together, but I also wanted to see what it was like living on the track together for a long period. Why? I wanted to see whether someone like me could do it and enjoy it – a fairly average someone, with neither peak fitness nor strength. Someone with good outdoor skills, but of average determination and resilience. Why? Because I could then perhaps inspire others like me to do the same. Why? Because that would make me feel good! This crystallised as we walked.

Geoff relishes the serenity of immersion in wild areas. The daily routine of long-distance hiking amplifies this immersion, and the experience becomes a series of walking meditations.

Your motivation as a slower hiker is likely different to Geoff’s or mine.

Perhaps you’re older, and have left that competitive spirit behind. Perhaps you enjoy being in nature, or are a botanist, geologist, ornithologist, or any scientist who is in their element while walking.

Cartoon by Rosemary Mosco https://www.birdandmoon.com/comic/naturalist-hike/

Many leisurely hikers will relate!

Or perhaps you are someone whose aesthetic eye is gladdened by vast natural vistas not found in cities: artists and photographers love hikes like this.

For hikers with personal or relationship issues, it may be time in your own head to heal and process, and perhaps to succeed in a challenging task to rebuild your confidence and self-esteem.

Others are on the track for mental health: being in nature is a great tool for managing stress, depression and anxiety, and some hikers regularly spend time on long distance hikes for this purpose. Without tasks other than a few simple daily routines (eat, walk, sleep), life is less complex.

Some couples are on the track for a shared experience; other hikers are solo introverts who prefer to keep to themselves.

Hikers aiming to build strength and fitness or to lose weight can be certain that, however far or whatever speed you hike, it is doing you good. Regardless of your weight or shape at the end, your health will be better!

Whatever your motivation, it is yours, and is as valid as anyone’s. Make sure you understand it well so that you can draw on it to sustain you on those challenging days.

3. Planning

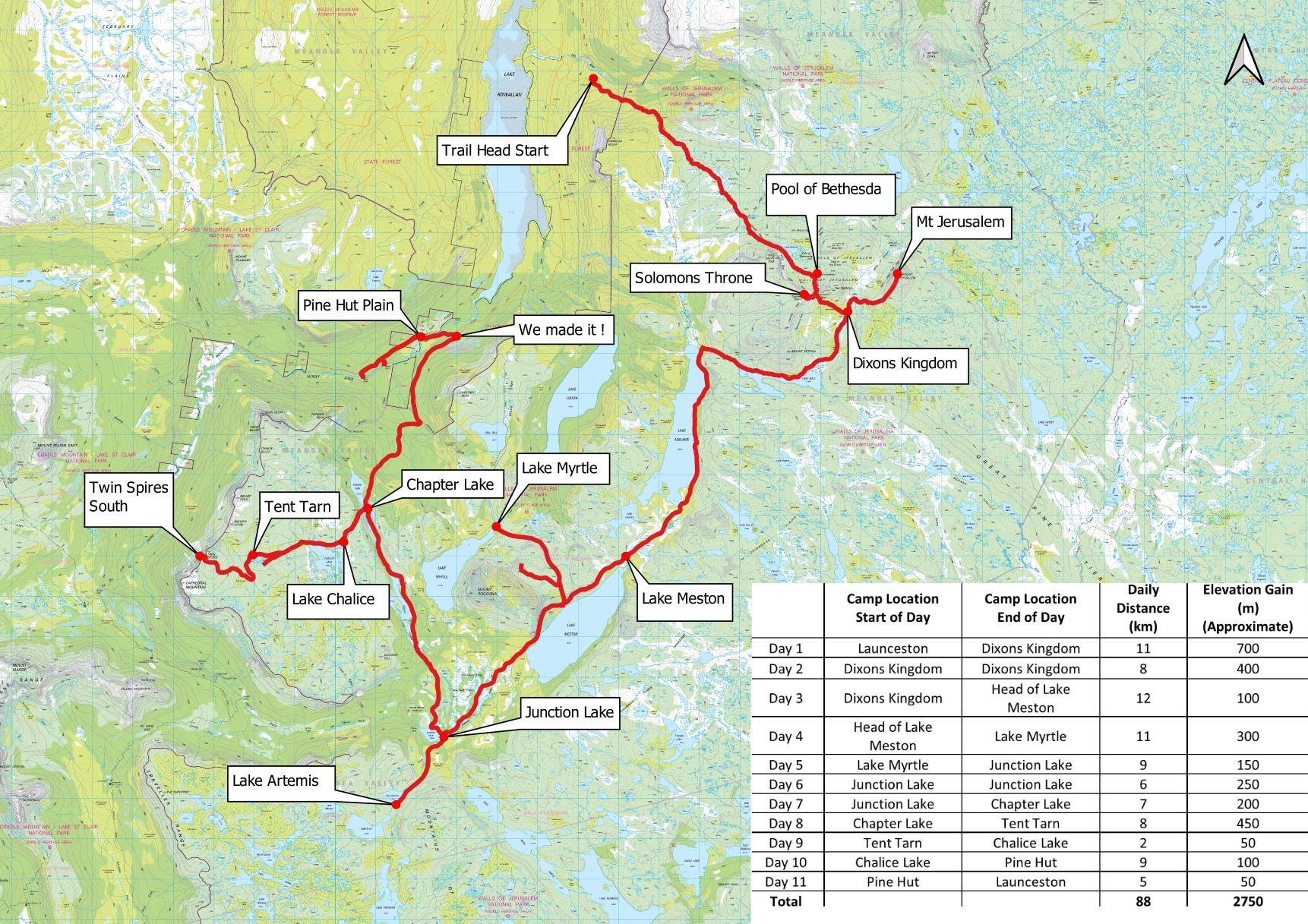

Maps can be fun! Here is our composite map with printed route of our 11 Day Walls of Jerusalem Tour.

Buy maps and/or mapping apps, and learn how to use them.

Gather your gear and supplies. Organise your food. Here are some tips from our Bibbulmun Track experience.

How does this help motivation on the track?

Any planning and tasks you do before the track are planning and tasks you don’t need to do on the track. You won’t need to buy and repackage food if it is already in your resupply box waiting for you. If you’ve also packed toilet paper and toiletries, it’s another thing you won’t need to organise on the track. Even with resupply boxes, one of our ‘rest days’ in town was still filled with washing, recharging batteries, packing food etc.

It’s amazing how long it takes to repack your gear and double check everything… even without needing to find and buy it.

4. Nutrition as a Motivator

Reward yourself and your body daily with good food! Although some people lose their appetite when hiking, others get grumpy when they are hungry. You may get by on instant noodles and cup a soup, but most of us feel and perform much, much better eating a balanced nutritious diet with sufficient protein. Your brain consumes an enormous amount of energy, and well-nourished long-distance hikers are more likely to make good decisions, and to maintain positivity.

Use RADIX10 Coupon Code at checkout for a once-off discount on all Radix products that are not already discounted.

Geoff and I get no kickbacks from Radix other than the same one-time Coupon; we just think their protein powders are great for hikers!

(Image Credit: Radix Nutrition)

Both Geoff and I suffered unnecessarily on our Bibbulmun thru-hike due to insufficient protein, and we quickly noticed the difference when we started eating more of the latter. We’ll be adding more olive oil and protein powders to our food/diet on all longer hikes from now on. Milk powder, chickpea and lupin flours are cheap alternatives at around 40% protein, or about half that of the protein powders.

For more info, Gear Skeptic has super-informative, in-depth videos about nutrition, food weight and meal planning for long-distance hikers.

You’ll get stronger more quickly, and stay stronger, on a good diet. Pre-organising food also gives you control over variety, so you can choose the things you like eating most. This preparation is likely to make your time on the track more enjoyable, and thereby help you stay motivated.

Even if you decide pre-preparing is not for you, and you prefer to buy resupply food in each town, you can research what’s available to know what to look for in the supermarket or pharmacy, and how you can adapt them to be more nutritious. Remember, this is not for a week or two: this will be your diet for months, so it’s worth making healthy choices.

4. Preparation for You and Your Gear

If you can, train, as far ahead as possible. Walk everywhere with a backpack, building up to the weight you’ll carry on the hike. Bottles filled with water are convenient: you can empty them if you want to return with shopping, or if you’ve been too ambitious and it’s too heavy!

Walking yourself fit on the track works for many people but, for very unfit folk, the first weeks can be so punishing that they simply give up.

Therefore, if you’re particularly unfit, and motivation to train is hard to find, consider mentally moving the official start date 6-8 weeks ahead. Whilst you’re still at home, start walking whenever you can. Carry that pack every time, not just for fitness but to reinforce that ‘already started’ motivation. Each step you take now, before your hike, makes the first steps on the actual trek so much more fun!

On your training hikes, test the pack, clothes, and especially shoes and socks you plan to use (no new boots on the track!). If you haven’t done any overnight hikes before, try a one night “shakedown hike” locally, carrying all your gear to check it functions correctly. If there are any issues, adjust as necessary and try again.

Make training fun. We used our six day hike on the Investigator Trail to fine-tune food and practise dune hiking.

Try daily distances similar to what you expect to cover on the first part of the track. Flat ground is not the same as mountainous terrain! Some people use resistance training, or specific exercises such as squats, lunges, calf raises, step-ups or stair climbing to build muscle strength.

How do these things improve motivation on the track?

Many people leave the track because, in that first fortnight, their gear does not function as it should. Their tent leaks, their cookstove fails, their pack is too heavy, their sleeping gear is insufficiently comfortable or warm. Their boots give them serious blisters, they develop ligament injuries. Forget joy, this is awful, they think! Everything on a first thru-hike is challenging, without adding unnecessary stressors.

Wet Boots!

No bother, it’s putting on the wet socks the next day that’s the challenge… so get good socks!

You can prevent all these common motivation-killers with a simple shakedown hike(s).

Other people leave through injury, and this is much less likely to happen when you are wearing familiar footwear, carrying a relatively light pack, when your muscles are strengthened, and when your body is accustomed to the slightly altered biomechanics of carrying a pack.

For various health reasons neither Geoff nor I were able to train to the usual degree before the Bibbulmun Track. However, we completed it without injury anyway, so don’t beat up on yourself if you can’t train as often as you hope. Every day you hike or even just wear your pack whilst shopping helps, and is always better than nothing.

Be kind to yourself. Just do what you can, and know it will make a difference, just as any pre-planning makes a difference. Which leads us to the next tip.

6. Customise Your Itinerary

For leisurely hikers, the keys to customisation are to make time for the things you enjoy, to be conservative in your scheduling, and to start slowly.

6.1 Make Time for Things that give you Joy

If your joy on the track comes from hiking as fast as you can, then schedule for that. For any other motivation, reconsider.

For me, wildflowers and views are paramount: it was amazing how a new orchid discovery at the end of a long, tiring day bounced me along those last few kilometres of track!

When you’re a naturalist, a hike is a treasure hunt. There are wonderful discoveries to eagerly anticipate every day, and you never know what is around the next corner. Prior research can be a map for your treasure hunt, further increasing anticipation.

A very muddy echidna

If at all possible, schedule your hike for plenty of time to spot shy birds and animals, or to photograph flowers. To fossick for rocks. To sketch that perfect scene. To simply be in nature. To get up early to catch those mountain top sunrises, if those are what fill your heart. To share laughs around campfires with wonderful people, and to develop deep friendships. Sharing beautiful vistas and new experiences, rather than experiencing them alone, invigorates Geoff and me, and our relationship.

And what would be the point of completing the distance without joy?

6.2 Schedule Conservatively

As a new hiker, give yourself more time than you think you need. There will almost certainly be unforeseen delays due to minor illness or injury, and rushing to a deadline is the last thing leisurely hikers want.

We didn’t expect this delay - having to make our way around a prescribed burn!

Not everyone has this luxury but, if you’re taking time off work, an extra week can make the difference between a fun hike and a harried one, not just during the hike but afterwards, when you have time to transition into work mode again.

When you hike for consecutive weeks and months at a time, the rest days – your ‘weekends’ - are important. Most thru-hikers spend two nights/one day in towns. You arrive the first evening, spend the next day in town, sleep a second night and then leave. However, this is rushed. Your day in town is usually spent on a myriad of small but important logistical tasks: washing clothes, collecting and unpacking your resupply box, shopping for fresh supplies, eating (lots of eating!), ringing or emailing friends and family, updating social media, paying bills, charging batteries and replacing or repairing damaged or lost items.

Another unexpected and enjoyable town meal, this one at the local Northcliffe Workers Club on the Bibbulmun Track

Murphy will decree that the laundry is at one end of town and your accommodation at the other. The pub is somewhere else again. You may spend a few hours just walking up and down the main street! You’ll be amazed how quickly your rest day passes, and is not restful at all!

Many won’t have enough time for the following, and it may not work for hikes in the Northern Hemisphere when you run into winter but, after a tip from another couple on the track, we tried three nights in each town. It made a huge difference. We had one day to complete tasks, plus one day to really relax. The next morning, we were both eager to get back on the track:

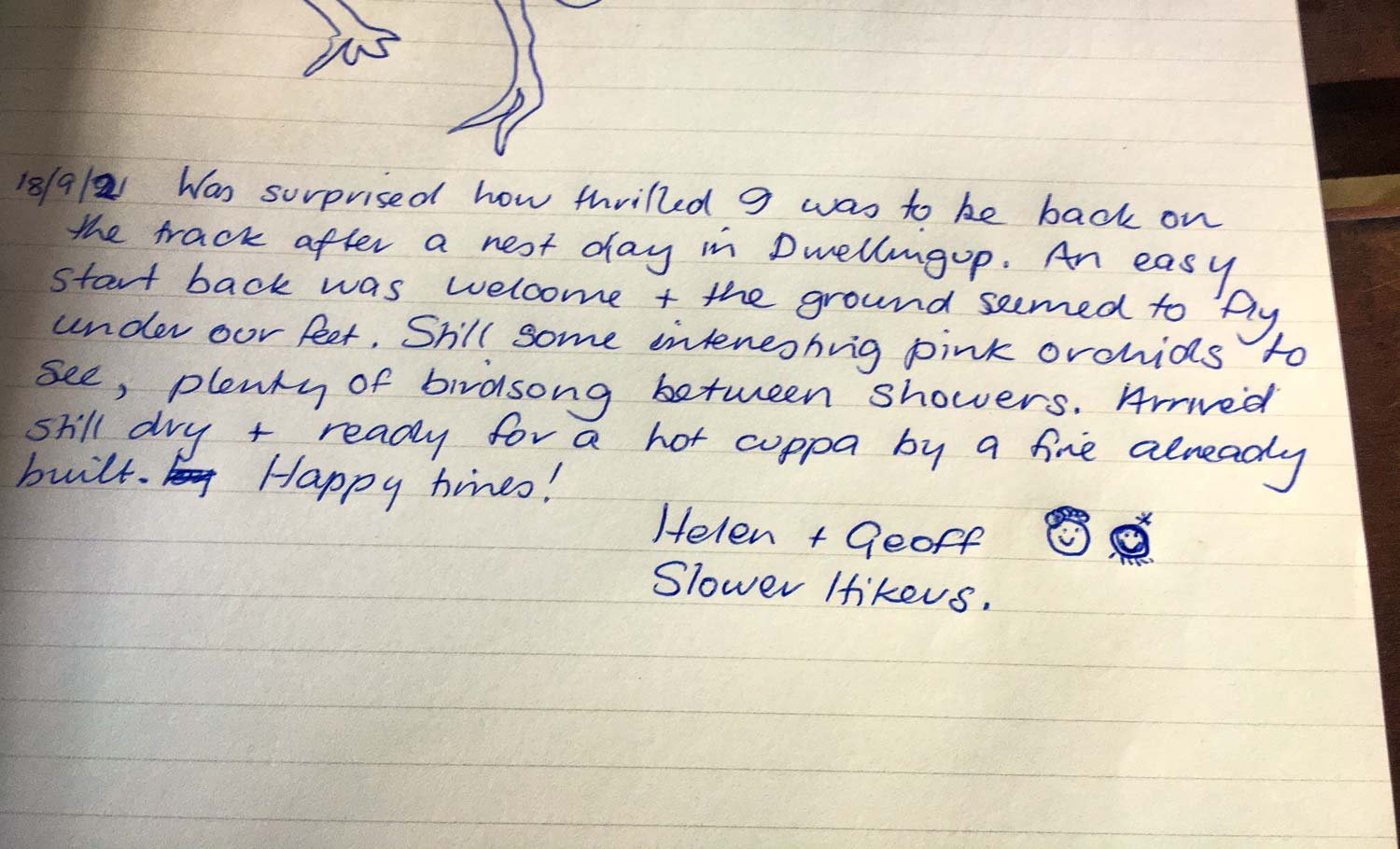

Our note in the trail log after a town rest day…

a little different to the day before the town!

6.3. Start Slowly

Everyone tells you to start slowly, but even a relaxed hiker like me wondered whether we should push on when we reached one of the northernmost Bibbulmun huts early afternoon. But no. Geoff reminded me that we had made that mistake before. So we pitched the tent, had a relaxing cuppa and lunch, fossicked around camp and pulled out the playing cards.

Winners are grinners!

And Helen won all the games!

Walking for one or two weeks is not as tough on your body as a thru-hike. You have little time to recover; your joints and ligaments are placed under enormous strain simply by walking all day, every day, for months. Let them strengthen in those first few weeks; there is plenty of time to speed up if that is what you want. Prevent little injuries from worsening by giving them time to heal. In that first 7-14 days, set a conservative itinerary and stick to it.

6.4. Flip-Flop Thru-hiking

On very long thru hikes, particularly in the northern hemisphere, slower hikers who can’t start in very early spring or late winter may run out of time as they enter the next season’s winter conditions that make the trail impassable or dangerous.

The season was late and there was still a lot of snow on this Dolomites hike.

Without spikes or ice axe, and a drop off below, this was more challenging than we had expected… so we just took it slow and steady and it was all okay.

A flip-flop thru hike is a fantastic option for leisurely hikers. It means not starting at the usual terminus, but somewhere in the middle. You hike in one direction, before typically returning to the same spot and hiking in the opposite direction to complete the trail.

In the northern hemisphere, where conditions are too snowy to start in the north in spring, hikers start midway and head north, so you hit the coldest regions in summer. You then get transport back to the middle and hike south towards milder climes. You hit the coldest regions at the warmest time of year, and the warmest regions at the coolest time of year.

Flip flops can be designed around any section that is problematic in certain seasons – high country ice, spring snow melt flooding, summer bushfire season, or mud season in low lying areas. Or, rather than flip-flopping, you skip the problematic section, and complete it later. Flip-flopping is also an option if the season is unexpectedly late or early.

Fire warning sign on the door of a Bibbulmun Track Toilet.

It’s not a good idea to hike this track mid summer! Even when we hiked in spring there were wild fires and prescribed burns that impacted our hike.

Long thru hikes often have well known flip-flop itineraries that you can adapt to suit your pace and the season. The key point is not to get locked into conventional approaches unless they suit you.

Folk who prefer solitude may also appreciate a flip-flop thru-hike because most walkers follow the conventional end to end itinerary: you’ll be on different parts of the track in different seasons.

7. Decision-Making around Chronic Conditions

Some chronic inflammatory conditions can flare up on the trail. Should you even start on a thru-hike? It’s a personal decision that you should make together with your medical practitioners, getting a second opinion if you don’t like the first answer.

Modifications to manage foot problems.

Knowing your body and what it needs will help you stay on track. And Hypafix is hiker gaffer tape!

However, if you remain unsure, with an ambivalent health professional, ask yourself:

What would you regret more in five years’ time: going but having a flare up, or not going at all? Not the regret while you’re in the flare up, but in the years afterwards, because it’s often the things we don’t do or attempt that we regret the most, rather than the things we do.

Is there potential for treatment during the trek, or for you to take a week away to travel to treatment? Can drugs or treatment be sent or organised by your health professional to local clinics or pharmacies? Are alternative medications (eg those that require no refrigeration) available for when you’re on the track?

If you do get a flare up, are the effects temporary, long lasting, or permanent? Expensive? Horrifically painful? Are there potential impacts on employment afterwards?

Only you know how much you are prepared to potentially bear. None of us can tell you. Another way to look at it: if you knew you were definitely going to get a flare up, would you still go? Some people think it’s worth it, so will have a contingency in place, and that’s another way to view the decision.

It’s not just the walk itself that is precious, it’s the memories you build… and they last a lifetime. Such experiential memories are priceless and often it is worth the effort and sacrifices to make them. So, weigh up the joy, experiences and memories for a lifetime on one side, and potential pain, regret and permanence (or not) of health / life impacts on the other.

Even in wild weather beauty abounds: literally gale force winds this day, and the sea and sky were magnificent!

8. Realistic Expectations

When you hike daily week upon week, the walk becomes somewhat like a job. A wonderful job, to be sure, but a job nonetheless. Online videos and blogs generally comprise only highlights, but there is a lot of country between those highlights, and some of it is boring or unpleasant. No one takes pictures of the boring bits, nor is every step exciting! There will be miserable days when it’s bucketing rain, but you still have to get up and start walking.

It’s still raining. 23 mm rain all day was less than exciting, but we would certainly remember it! Expecting days of rain is reasonable when hiking over several months!

One Bibbulmun Track Foundation mentor told us that, in their experience, it was often younger men with expectations that the walk would be a doddle, who gave up after a week or two. When you expect everything to be perfect, exciting and physically and mentally effortless, any setback or dull bit is a disappointment.

Understand that, at times, you will be bored, exhausted, sore or in a bad mood. There will be times when you take the wrong turn and have to backtrack. That is perfectly normal. Consider what life at home brings. Are you eager to go to work every single morning? Does every day bring something scintillating? Do you sometimes have crap days? On the track, life remains life. It is what it is. Be ready to accept it. The one certainty you have is that every day will bring something different!

You might like to brush up on or try meditation/mindfulness/breathing exercises. If this works for you, regular practice before and during the hike, even for just five minutes at a time, will increase mental resilience and help you to stay motivated. ‘Pushing North’ by Trey Free is an excellent read for a deeper understanding of mental resilience for long-distance hikers.

The Bibbulmun Track’s ‘infamous’ green tunnel… for some. However, having grown up in a treeless, arid area, Geoff loved it! And I loved it because there were still exciting new plants to see!

9. Make The Hike about More Than Yourself

If you think that you’re the kind of person who might give up when things get tough, consider making the hike about something bigger than yourself. Choose a cause that is close to your heart: set up a GoFundMe Page. Telling lots of people about your hike, and knowing that you’ll fail your cause should you give up, is a powerful motivator.

Even if you don’t want to fundraise, telling friends on social media what you plan to do, and promising regular updates, can also help keep you on track.

10. Address Your Fears

As a hang glider pilot, I’ve attended female pilot workshops on dealing with fear. One key is to identify whether your fear is rational or irrational. You can learn how to identify which is which in discussion with trusted, reputable people more experienced and knowledgeable than you. If it’s rational, take clear and positive steps to address the fear. This often involves researching the crap out of the issue, or to follow the advice of your more knowledgeable mentor.

If it’s irrational, with no foundation in statistics, remind yourself that, regardless of what your fear suggests, you are in no danger. Make a conscious decision to act based on your rational brain or trusted mentor rather than on your fear. Being scared at night by either the extreme quiet, or the noises made by harmless animals, is one such common fear. It is simply a new experience and, when nothing terrible happens in that first week, most hikers quickly become accustomed to the difference, and even begin to love it.

Little noisy creatures like this bandicoot aren’t dangerous!

A psychologist can teach you how to manage such fears if they are seriously circumscribing your life: often, they are deeply rooted in past experiences that take some untangling. For other people, simple techniques such as taking several deep, slow breaths, persevering for a certain set time longer, or reassurance from trusted mentors, is enough to get them through the crisis. This series of videos by a psychologist hiker are excellent.

Snakes and Other Animals

Be alert but not alarmed!

Some simple precautions will keep you safe.

In Australia, many people are afraid of snakes. You can completely eliminate the risk of snakebite on the lower limbs (by far the most common site) by wearing boots or shoes with gaiters instead of sandals. Understand that Australian snakes don’t have enormously long, needle-like fangs that penetrate everything. Even in the vanishingly small chance you are somehow bitten, correct First Aid is enormously effective: no victim with pressure immobilisation and proper aftercare has died.

Few Australian snakes are aggressive: stand still, and soon they’ll move away (unless they are accustomed to people, in which case you can quietly make a large detour around them or, if some distance away, stamp your boots and wave your arms to encourage them to leave). Hikers who use trekking poles are likely to see fewer snakes due to the additional noise and vibration they make.

The notorious Eastern Brown sees any movement – including you backing away – as a threat. It’s known to chase people, but stops and leaves if you stand still, and your best initial reaction, no matter how close you are to any snake, is to STOP. When Geoff or I see a snake (it’s usually me as I’m ahead and scanning for plants) we simply say, “Stop,” in an even tone. Saying this instead of “Snake,” helps reinforce the action, and we both know what the word implies.

On the Bibbulmun, one hiker told us how that day, she had stepped on a highly venomous dugite snake that was eating a frog in the middle of the path. The snake may or may not have struck at her – there was flailing and jitterbugging for a moment, before the snake disappeared. No one can or should stand still in that situation, but take confidence in the fact that gaiters work. For additional reassurance, learn the correct first aid.

Ok mate… the track is yours!

Well actually, we simply waited until this beauty realised we were there, and she fled.

Protocols for bears and other large, dangerous animals are well established. Follow those protocols.

Ticks, leeches and spiders also have standard preventatives and treatments that minimise your chance of being bitten, and the after-effects if you are.

Other People

Although many women feel no differently than do men while thru-hiking, some solo women feel particularly vulnerable. Invariably in discussion groups someone dismisses their concerns. Please don’t. The risk is very small, but real.

Consider what gives you confidence. In some countries, that might be pepper spray. Or you can team up with another hiker until you gain confidence, meeting up at certain times of the day and/or evening.

At a Bibbulmun hut with just Geoff, me and a younger solo female hiker camped for the night, a man appeared on foot, without gear, and began asking the solo hiker highly inappropriate questions. He was “in his caravan nearby, with his wife.” He wanted to take a photo and we posed, but Geoff and I more or less stood in front of our hiking companion. All our instincts were on alert. He disappeared, then skulked in from a different direction, before leaving for good.

His story may have been legitimate, but consider how you would handle such a situation alone (some women leave to stealth camp further down the track, or spin stories about non-existent male hiking partners following behind, or are assertive about wanting their own space, or ostentatiously carry pepper spray). At the same time, remind yourself that, around the world, long-distance trails are extremely low risk environments for attacks, and you are likely more safe on them than in a city!

Which way Helen?

Other than for regular weather updates, we only used our inReach Mini (on Helen’s shoulder strap) once during the hike to get bushfire information via family. Good to know that it was under control and well worth the 100 gram investment!

Leave a detailed itinerary with a reliable friend, and carry an Inreach or other satellite messenger to check in regularly, or allow tracking. Move assertively at trail heads to give the impression you know where you’re going and what you’re doing. Choose popular trails initially to gain confidence. Skip earbuds to retain situational awareness, take a self-defence class. Go for short overnighters to build your confidence. Alternatively, attend an overnight hike training course run by the relevant trail association.

Some solo women hikers fill out the log book with their initials, under a male or neutral name, or not at all (inform your reliable friend of your alias). Listen to your instincts. Being prepared with these tools reduces your fear and increases your self-reliance and motivation once you’re on the track.

Challenging Terrain

Seriously exposed sections of track can often be avoided by rerouting, particularly if you are a solo hiker. Learn techniques to hike safely, such as how to recognise and traverse dangerous slopes, snow or water, for example: how deep is too deep? What flow rate is too fast? At what corresponding depth?

I thought I told myself not to look down!

Will specific gear such as mini spikes, poles or ice-axes make for more secure footing? Do you know how to use them? Do you have cell or satellite reception should things go wrong? Checking in regularly with someone who has your itinerary, or switching on tracking of your satellite communicator, greatly increases safety, and you’ll be less likely to give up when you hit those challenges if you have the skills, equipment and backup already in place.

Long distance thru-hiking is as much about mental resilience as it is about physical resilience. Prepare yourself in both, and you will succeed!