Human Factors, Decision-Making and Hiking Safety: What You Need to Know

For many of us, a degree of challenge is what makes a hike fun. The balance of challenge and fun depends on our risk tolerance and is different for everyone, but we all want success and to return home in one piece.

Hiking safety is something we all aim for, and most of us know the basics: leave an itinerary, carry a PLB and first aid kit, check weather forecasts, choose appropriate clothing and gear for the weather and terrain you expect to encounter, choose a hike within your skill envelope, hike with a buddy. All these things are covered to the nth degree in online articles and forums. Gear and environmental (terrain and weather) factors are important, but there is one essential component to hiking safety that underlies everything: you!

This article series is not to dissuade you from hikes that challenge you, on the contrary: it aims to provide you with mental tools to try challenging hikes with confidence and in the safest possible way. Once you understand how the brain and situations can trick you into making poor and potentially risky choices, you can counter these tricks for more objective, rational decision-making.

This article, Part One, covers the human factors — particularly our own minds — that negatively affect decision-making and safety when hiking. This article explains WHY we make poor decisions.

Part Two will address HOW to assess risk and HOW to make better decisions.

And future parts will link experience, environment and gear to specific situations for WHAT good decisions might look like.

Most serious hiking mishaps happen due to human factors: emotions, fatigue or decisions that we make, rather than gear or environmental factors in isolation. Serious mishaps often occur not due to a low skill, experience or knowledge level, but because we are attempting to operate beyond them, whatever that level happens to be. That’s why hiker deaths span the range from inexperienced tourists on day walks, to experienced veterans in remote regions.

As well, many hiking accidents occur not in extreme conditions but moderate ones, or moderate ones that later become extreme. This is because we are likely to make good decisions when weather is extreme: no one is going to start hiking to the top of a mountain with lightning crackling around the peak! However, the decision is more complicated when the peak is clear, but we see thunderclouds in the distance. The storm could dissipate before it reaches us, or travel in a different direction. What do we decide?

What about cool, wet conditions? Temperatures are only around 12C/54F, but it has been raining heavily. Our gear fails and soon we are drenched to the skin and shivering uncontrollably. Do we keep hiking to our planned campsite because really, it’s not that cold? Some people stop to assist – how embarrassing! – but we wave them on. We can manage. Or do we cut our day short and set up the tent? If so, when?

In Australia, water is often scarce and hyperthermia/heat stroke and dehydration can kill almost as quickly as hypothermia. It’s 36C/97F, we’ve run out of water and we’re not sure if the tank is full at camp. Should we push on the shorter distance or backtrack the longer one?

Hot and dry conditions in Little Desert National Park, Victoria

We’ve been planning this walk for a long time and now the forecast is rubbish. But we may not have another opportunity and flights and accommodation were expensive. Surely it will be alright? We’re already at the trailhead, raring to go. What will our Instagram followers think if we bail now?

Or perhaps the weather is worsening but we are nearly at the peak: we might as well summit now that we are so close, rather than turning around.

We may incorrectly assess terrain or fast-changing weather, and conditions exceed our gear’s capabilities. We may misjudge our stamina and speed, and find ourselves hiking in darkness on exposed track or through thigh deep snow, with expected hiking time quadrupling as exhaustion or hypothermia cloud our ability to make rational decisions. We may also overestimate our ability to make calm choices while under pressure, when sideways sleet combines with a wildly flapping tent and frozen fingers and everything quickly turns to sh*t.

Genuinely freak accidents devoid of human factors are rare, but this is one. More often, tree falls happen during storms or after bushfires, when tracks are often closed. (Image Credit: C/- Martin Gotthard)

-

“There’s no such thing as bad weather, just bad clothing,”…until a tree comes down right on top of you and your hiking partner!

My closest-ever call. Part of the tree came down in front of my face, close enough to take my hat and glasses off and give me scratches. It crushed my foot. The other part came down on my pack, driving the frame through the top. A centimetre or two in either direction and I’d have been dead.

The picture is of my friend’s pack, speared and gutted. She was, happily, uninjured.

Lesson learned: There are some hazards that good equipment doesn’t mitigate. Definitely.I got First Aid at the Parks Office and discussed options. My foot was pretty rooted, but we decided not to take the only ambulance – based at Queenstown –for what would be 12+ hours for a limb trauma. Instead, the rangers drove my car as far as Ouse where the road improves, and for any delayed shock reaction to present with my hiking partner. My hiking partner drove the rest of the way.

I had multiple broken bones in the front and middle of my foot, including my big toe in a few places: pretty hamburgered. Fortunately, everything healed without needing surgery; crucially the ligaments were intact, which was extremely lucky and probably down to wearing full boots.

The decisions we make to hike safely and avoid danger start long before we are in the dangerous situation. Almost always, hiker fatalities arise because of a string of multiple small, seemingly unrelated decisions that we have made in the leadup to disaster. In hiking, the number commonly cited is just four poor decisions. If any one of those decisions had been made differently, it’s likely that disaster would have been avoided. It is known colloquially as the Swiss cheese effect (the holes in the cheese safety slice barriers all line up and the participant passes through them) and, during my time as Senior Safety Officer for our hang gliding club, I saw it in every serious accident.

Understanding Your Brain

Our brains like to play tricks on us: we often don’t know what we don’t know. We see things that confirm what we hope for or believe, and overlook evidence that contradicts our biases. We think the bad things that happen to other people won’t happen to us. We see other people hiking the trail we are on despite atrocious weather and assume it must be okay because look, all those others are doing it! We are afraid to share our concerns because we assume our hiking buddies know more than we do, so what we’ve noticed must be inconsequential or irrelevant, and we don’t want to be the worry wart. Understanding and recognising our brain’s tricks – tricks that are so ubiquitous that they have all been named – can help us to make better, more objective decisions.

High risk activities such as sport aviation, mountaineering and climbing all recognise the importance of human factors: they are included in formal training. Hiking is certainly less risky, but many of us also take part without any formal training, learning as we go. As we accumulate gear, confidence and navigational skills and begin to venture into longer, more remote and more demanding terrain and conditions, it’s essential that our understanding of human factors and decision-making improves alongside. If it does not, we are more likely to place ourselves in dangerous situations without realising we are doing so, or only realising when it is too late.

A remote camp in the highlands of Tasmania. We saw no one for four days of our eleven day hike, and just one other group the previous day on a different route.

A challenging hike is relative to your experience and ability level, not absolute: some hikers skip through what Geoff and I find tough. As older folk, we are conservative hikers with a lower risk tolerance than others. However, because challenge is relative, the same principles apply to hikers of every ability and risk tolerance level.

Preparedness: Decisions Begin before the Hike

Most veteran hikers love topographic maps. Learn to read them!

Social media now let us vicariously enjoy pretty much every hike, anywhere. Often, these influencers inspire us to try a particular hike, not least because they make it look so easy or, for those who thrive on challenge, because they make it look so hard! Remember, though, that what you see is curated, and never the whole picture.

You’ll review the gear and equipment you need for the hike, elevation profiles, daily distances, track condition… but you must also assess yourself, with clear eyes. Slowerhiking readers may be less gung-ho than bulletproof young bucks fuelled by testosterone and muscle!

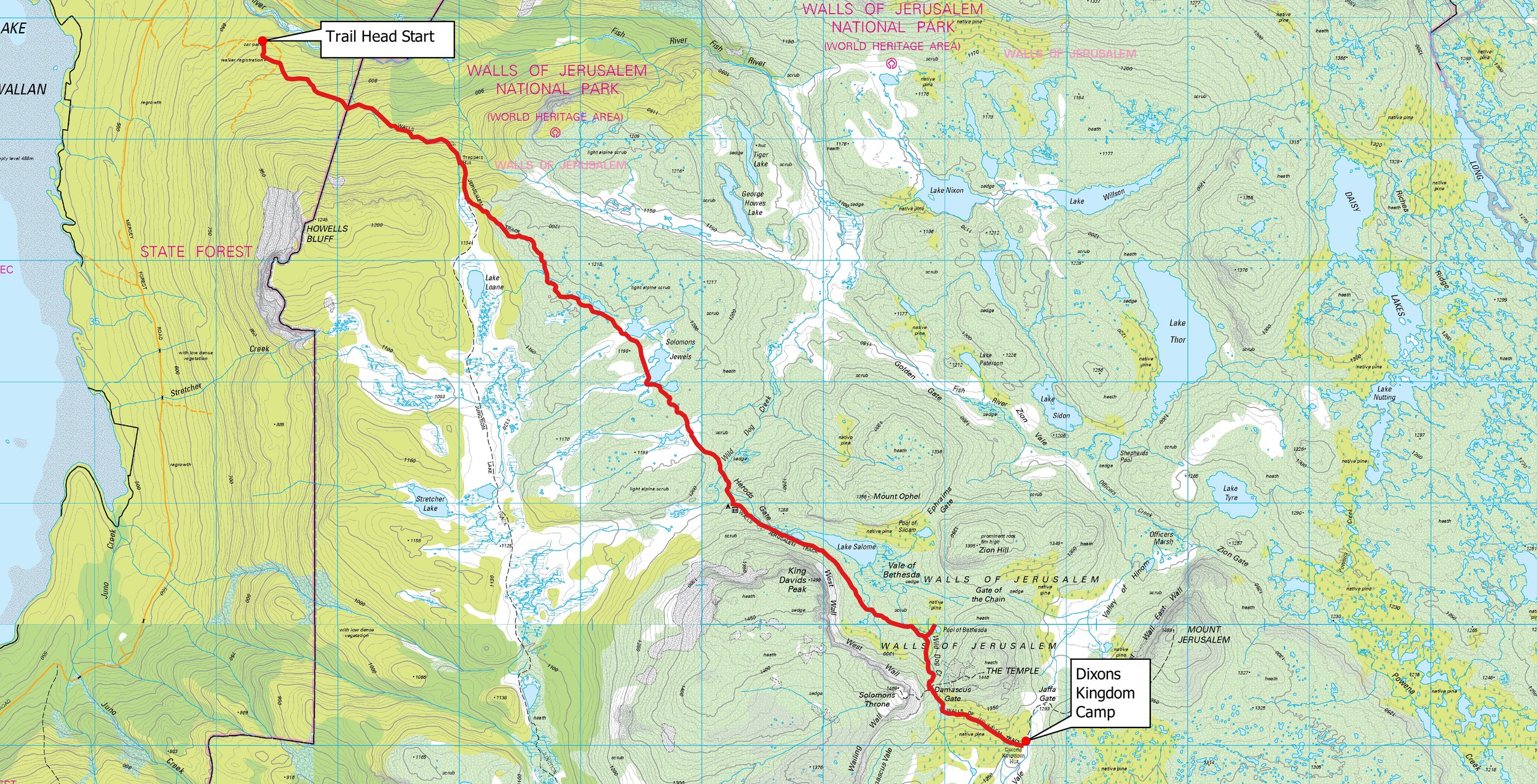

When you are considering a challenging hike – and we use challenging in relative not absolute terms, ie, challenging for you – watch videos, read trip reports, study topographic maps and buy a reputable guide book; in Australia, John Chapman’s works are deservedly lauded, though his hike times are way too optimistic for slower hikers!

And although PLBs and satellite communicators have somewhat altered protocols, there’s still much to be said for the original gold standard team of four people when you expect a high level of challenge in a remote area (we’ll discuss this further in Part Two).

Enroute to High Moor, Western Arthurs Track (Image Credit: Guilherme Salum)

We had planned to hike the Western Arthurs, including booking the trail but, after a few other demanding hikes, I had to acknowledge the painful truth that I was simply not ready. The terrain is so steep and the trail so rough that hiking into the night to reach camp would be risky, with no intermediate campsite bailout options. There is a lot of scrambling, much of it exposed. I needed to build more strength and fitness, lose a few kilos, and dip my toe into easier (but still challenging) hikes like the South Coast Track and Frenchman’s Cap first. Now in better shape and after hiking these other tracks without issue, we’ll revisit the WAT next season. Even so, I’m not a fan of exposed scrambles, so rope training will build confidence. And still, when the time comes, we may decide not to go. Assess and address your limitations, not just those of your gear:

Incremental skills training with a nearby hut for backup: build on formal training in a sensible, safe way. (Image Credit: Nicole Anderson)

-

Cold weather preparedness and building on training gained in formal courses has helped me enormously.

Knowing the reputation of Tassie snow and associated risks, I decided to undertake polar training in New Zealand and Antarctica as part of my wilderness medicine training. This boosted training from being a northwest Tasmanian Remote Search and Rescue volunteer.

I then trained in solo snow survival skills with combined skills and excellent equipment, but within a stone’s throw of a hut in case mentally or physically it became too difficult. I loved it.

The next night, I hiked further from the hut and adapted my camp plan for the forecast freezing rain by digging a snow cave: incremental skills-building as well as building mental resilience and self-sufficiency. This means that when I venture out on cold/snow trips with far more equipment, I’m comfortable with my survival chances should things not go to plan.

Nicole was proactive in getting training, and then building on those skills. How else might you build skills incrementally for a specific hiking challenge (eg scrambling, water crossings, remote offtrack routes)? (Image Credit: Nicole Anderson)

A cosy nest in a snow cave. Quality formal training gives you the skills, knowledge and confidence to venture into conditions with tools and equipment to ensure you do so as safely as possible should things go wrong. (Image Credit: Nicole Anderson).

Value Local Knowledge

I witnessed a fascinating phenomenon when a young person posted on social media a planned hike of a notoriously demanding route, including photos of their minimalist gear. The post was made after they had already left home. Hiking groups in a different state generally responded positively: “Go for it!” However, members of hiking groups local to the region were, to varying degrees, horrified.

If consciously hiking into challenging conditions, we need to understand every aspect: gear, track condition, weather, terrain and ourselves. Only one needs to fail for all to fail, and it’s no surprise that many hiking fatalities comprise tourists who are experiencing unfamiliar weather in unfamiliar places in unfamiliar terrain; it highlights why we should always heed the advice of locals.

In the Dolomites in unfamiliar terrain, under time pressure because of the weather. We consulted no locals. We are finally on track above, but had started across a boulderfield and gone completely offtrack (no pictures, I was in a slight panic). Rather than retracing our steps, we chose a ‘shortcut’ that took forever across the partially snow-covered boulderfield with countless ankle-snapping hidden holes. There was no phone reception and this was long before the widespread availability of PLBs; a broken ankle isn’t life-threatening but the resulting hypothermia can be. . Other tracks in the region were still officially closed for the summer as the season was so late in breaking (after we got back, we discovered this track was closed too). As tourists, we found it dismayingly easy to make poor choices.

When most locals are suggesting that our itinerary is overly ambitious and risky, we need concrete, objective reasons to ignore them. Are we world class athletes with skills above the vast majority? Have we had more experience than all of them? Do we know the terrain and weather better than they do? Or: do we not know what we don’t know? And which of these is the most likely answer?

In some outdoor and extreme sports, there is a phenomenon known as Intermediate Syndrome: an accident spike happens when participants have been active for long enough to consider themselves no longer novices. They have physically mastered the basics and are attempting more challenge, but they have not yet learned to reliably read the environment. Worse, they don’t know what they don’t know. Basics such as pitching a tent well are always the easiest skills to master, but you don’t hike in outer space: as we saw in the tents in strong winds series, there is weather, terrain, you, your gear and the complex interaction between them. This is the skill that takes longest to master, if indeed it is possible to master at all. The inexperienced hiker will struggle to pitch a tent in poor conditions. The experienced hiker can pitch the tent well in appalling weather on an appalling site. And the hiker who pitches their tent easily, because they do so before those appalling conditions arrive and at a better site, is a veteran.

We were testing the tent, and it took all our skill to set up in wind on shallow saturated sod over rock, with few loose rocks to use. A veteran would have stopped in the hut a kilometre or so back.

Over time, near-misses and accidents bring about a deeper understanding of risks, and your best chance of fast-forwarding your development is to listen to experienced mentors, who see all the things you currently can’t. And veterans can predict which new enthusiasts are most likely to have a serious accident: it is not those who are less naturally gifted, but those who, regardless of their skill level, ignore advice and continue to operate outside their skill level. The same applies in all high-risk sports, which hiking can be at a high level of challenge.

Mountaineering Scotland explains:

“Any sort of close shave should be a learning opportunity for you, with a clear look back on what happened allowing you to pick out the things you did wrong, or could have done better, the things you should have done but didn't and the things you did which you shouldn't have. The idea isn't to beat yourself up about how stupid you were, but to learn from your mistakes so you don't repeat them.”

The reports are worth reading, as are all the links in this article, as they are real life illustrations of theoretical concepts.

You’ll see the same wisdom in hiking forums and, to a somewhat lesser extent, social media hiking groups. These groups are, at their best, a marvellous resource to give you the best chance of success, though you may need to winnow responses! Of course make your own decision, but do so after giving serious consideration to veteran locals, particularly if you are relatively inexperienced yourself. If you’re determined to continue, a good compromise is to consider adding exit/bailout points into your hike; we’ll discuss this later.

Heuristics, Cognitive Biases, Other Human Factors and Decision-Making While Hiking

On that Dolomites hike, we didn’t immediately turn back when there was more snow than expected (we had never hiked in snow). We weren’t familiar with the weather and were soon in almost-whiteout, but had seen other hikers on a lower track. It was our first hike ever in the Dolomites and we were eager for new experiences in new places on a special (and expensive!) holiday. The list goes on: see which heuristic traps we succumbed to as you read on!

Those mental tricks mentioned earlier are known as heuristics and biases:

“Heuristics are rules-of-thumb that can be applied to guide decision-making based on a more limited subset of the available information. Because they rely on less information, heuristics are assumed to facilitate faster decision-making than strategies that require more information.” (American Psychological Association). We use heuristics automatically and subconsciously, because having to stop and think about every single action means we simply couldn’t function effectively in everyday life.

Heuristics often give rise to cognitive bias. “Cognitive biases can generally be described as systematic and universally occurring tendencies, inclinations, or dispositions that skew or distort information processes in ways that make their outcome inaccurate, suboptimal or simply wrong.” (Encyclopaedia of Behavioural Neuroscience 2nd Edition).

Therefore, although heuristics are excellent for allowing us to function in everyday life, they are terrible when making important decisions in high-risk situations, activities and environments, because they don’t take all relevant factors into account. And because many cognitive biases are also subconscious, they too lead to inaccurate judgments and irrational decisions.

Let’s take a look at some of the most common heuristics and cognitive biases that affect our decision-making whilst assessing risk when on trail. They are:

Familiarity

Acceptance

Commitment aka Consistency or Summit Fever

Expert Halo

First Tracks aka Scarcity

Social Facilitation aka Social Proof

These heuristics are often referenced by the acronym FACETS.

Familiarity Effect aka Normalisation of Deviance

This applies when you are familiar with a particular situation or environment, such as crossing a river or an avalanche-prone region many times. Or perhaps you expect a waterhole to be full because it always has been before. There is risk involved but, because nothing has ever happened, you become more complacent with each encounter.

This is a particularly insidious heuristic because we let down our guard, becoming less situationally aware and thereby increasing the risk. It is often seen in avalanche fatalities, with skiers and snowshoers of every experience level ignoring obvious signs of avalanche danger. McCammon writes,

“Highly trained accident parties tend to make riskier decisions in familiar terrain than in unfamiliar terrain… Remarkably, parties with advanced training that were traveling in familiar terrain exposed their parties to about the same hazards as parties with little or no training. In some respects, familiarity seems to have negated some of the benefits of avalanche training.”

Instead, treat the situation as new each time. Check conditions and surroundings with the same thoroughness and don’t assume that just because you did it before, it will be the same again. Use specific routines and a mental checklist done immediately before the risk, especially when you are under pressure, eg hurrying to beat nightfall or when your routine is disrupted, such as a distraction with recalcitrant gear. Have a Plan B – an alternate route, exit or turnaround point – and use it if a tick is missing from your non-negotiable mental checklist.

Unpleasant surprises can happen when reality doesn’t match expectations. Can you think of at least three strategies that would avoid the situation described below? (Image Credit: Yvonne)

-

A group of us hiked to Mt Cloudmaker, planning to spend the night in 100 man cave. The leader (me) had been there before, and knew there was a good creek at the cave. There isn’t any other water between the car park and over Rip Rack Rumble and Roar knolls to Mt Cloudmaker, so the cave water source was important.

We arrived at the cave hot and tired, only to discover the creek was completely dry! We followed it downstream with increasing panic before retreating to the cave. We adapted our menus and ate food that didn’t require rehydrating for dinner. Fortunately we found a few slow drips from the cave roof, so we set up billies and mugs beneath each drip and spent a restless night emptying collected water from our mugs into bottles.

By morning we had collected just enough water for a breakfast cuppa and to sustain us on the walk back to our cars. About an hour into our return walk we met a school group camped on the ridge - also completely out of water. Their guide had disappeared at dawn in search of water and not been seen for some time. We offered to call their school principal when we got back into mobile reception range. We had insufficient water ourselves to share with them.

Fortunately, we had stashed extra water in our cars, and we all needed a long drink when we got back! Lesson learned: don’t assume there will be water!

Acceptance or Conformity Effect

This operates at many different levels, and is also influenced by intrinsic personality traits. It’s the age-old ‘making decisions to impress others’, rather than for the situation at hand. Once primarily limited to ‘others’ in the hiking group, it’s now extended a thousandfold with the advent of social media, so that even solo hikers take enormous risks. Young men take more risks in a mixed group with female peers, potentially exposing the entire group.

In group situations, this heuristic also leads us into situations well outside our comfort zone because we’re embarrassed to speak up, or to admit we’re struggling, or we refuse needed assistance. Conversely, we may not raise an issue because we don’t want to be seen as the weak link, killjoy or worry-wart.

When we’re hiking in a group, a good leader always checks in with everyone and solicits feedback throughout the trip. Never be afraid to respond honestly: not only your safety but also the group’s may depend on it.

Hiking with a buddy is useful not only because a second person can help should there be an accident, but because two heads are better than one when making decisions, especially when you are in a group of peers and working as a team.

If you are faced with a decision on a hike and you feel embarrassment, beware: you are likely being affected by this heuristic because embarrassment is always in response to what you feel others think. A trusted hiking buddy with a similar risk tolerance will always listen and accommodate you, as you would them. As for strangers on the internet, is their opinion worth your life?

Commitment or Consistency Effect aka Summit Fever

On the Overland Track on Tasmania’s Central Plateau, January (midsummer). It’s hard to believe when you see an image like this that, at the exact same time of year, blizzards and hypothermia kill hikers who are certain that they can reach the next hut.

A light sprinkling at Pelion Hut in summer, pretty and fun like this, but much more can fall (Image Credit: Anthony Barton)

This is perhaps one of the most difficult of heuristics to resist, especially for those who thrive on challenge, and every experienced hiker has felt its effects. It’s when you continue to commit to a particular goal even when circumstances change and a different course of action is warranted. Worse, the commitment heuristic escalates. The more you commit, the harder it becomes to escape; you become locked into an increasingly certain path to disaster. Outdoor accident investigator Jed Williamson cites it as the number one reason for outdoor accidents in mountaineering.

For example, you plan to camp on a famously picturesque ridge, but you had a late start and are still several hours away. The winds are already howling but you should make it before dark… you think.

An hour later – it’s raining now too – you pass a small and unappealing but sheltered campsite. You glance at the sky as the wind buffets your pack and horizontal rain stings your cheek under the brim of your drenched rain jacket. But… only another 90 minutes to that amazing spot!

One hour later you stop again. Your pace on the slick, muddy track has become even slower and you are exhausted. You’d like to camp but the terrain is now so steep that there is nowhere to pitch your tent. Perhaps you could simply wrap it around yourself instead? Your last option for a campsite was that cramped muddy one all the way back, but surely better options must begin appearing soon? Yes, it’s horrendously windy, but by now it’s a shorter distance than turning back, and just 30 minutes away. It will also be more exposed and fully dark by then, but at least you know there is a campsite.

You’re starting to shiver – you’re drenched to the skin and have stopped for too long – so you trudge on. Half an hour passes but by now, shivering uncontrollably because you are moving too slowly to generate warmth, you realise that it will take at least another half hour because visibility is so poor in the dark and driven rain, but you can’t turn back, it is too late and the top must surely be just over that next ridge. Or is it? You’re getting a bit confused. Perhaps you should sit down and have a little rest? Because you can only keep going forward, or so you tell yourself for the umpteenth time in the last two hours.

This spectacular and superficially benign image belies the risks on the Laugavegur Trail. Tents at the campsite on the left of the lake are regularly blown to bits.

On popular tracks such as the Overland and Laugavegur, dead hikers are found with depressing regularity a short distance from huts with their tents still inside their packs: setting up a tent in adverse conditions is difficult, more so when you are exhausted, close to impossible if you add panic and hypothermia into the mix. Elsewhere (https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/mountain-death-extreme-example-of-a-string-of-poor-decisions-mountain-safety-council/YYEXHUTKGTECCBQWWMGKBGSS54/), hikers are simply found dead on the track. In unplanned night-hiking in treacherous terrain, we lose tracks and become increasingly disoriented, exacerbating the risk of fall injuries.

You pass a small cairn on the Laugavegur Trail where a hiker perished within cooee of Hraffnitussker Hut.

Commitment escalation narrows your options and increases your risk as you pass each decision point. Countless people have died while fixated on a pre-determined course of action that becomes more inappropriate with every step.

In the same way as for the Scarcity Effect, the best solution is to have concrete, non-negotiable exit points. For example, if:

I am not at this or that point by this time, or

the weather turns to this or that, or

the track becomes this or that or

the river is this or that

the snow becomes this or that or

my water supply is this or that

I become this or that

I will:

· stop/turn around/take an alternate route/do X.

Have a satisfactory Plan B prepared: it is easier to let go of your goal with a good alternative in your toolbox, and it will be easier to let it go early if you have non-negotiable exit points. Turning back is an option to always have in your toolbox.

-

“It was to be an easy trip. Safety gear but no rope or rescue gear. Hike fifteen kilometres down a couple of ridges, camp by a river and then ascend via an easy canyon, that apparently didn't need any gear.

The hike down was hard but lovely. We made easy time so the next day out should be no issues. We woke on time but walked slowly, stopping for swims. We hiked nearly all the way up and out without a problem before hitting a waterfall.

There was no easy way up except a scramble up a very steep fifty metre high rock pile wall. It was getting late and it was too late to reverse: we had to work the next day. So up we went.

I told my partner to go slow. We climbed ten metres apart to avoid rockfall and both being taken out. It felt stable enough until close to the top where the rocks started moving underfoot. They were large rocks and, to our horror, the entire cliff was unstable. If one rock went it would likely trigger a larger slide, and falling with the rocks that far would almost certainly be fatal.

Going down was more dangerous than up and made a rockfall even more likely. We had to move horizontally, testing each rock on the way. The last 20 metres of vertical took over an hour.

It was dusk when we reached the top, and we had to finish the ridgeline with headlights on a 20cm wide goat track with fatal drops on either side. We reached the car in darkness.

I got the job of converting the D of Education training package online during Covid, and it sent my coroner report hobby into overdrive when I wrote the sections on risk.

It made me reconsider why that little snafu happened when I never would have at work, and I realised how friends/partners can badly cloud our judgement. If I was at work and decided to benight a group and somebody said they had a meeting, or were hungry, I couldn't care less. The decision is made for a more important reason. We only second guess when we are reasoning with our own people (the Kanangra falls canyon deaths were people basically letting their friends tag along out of their depth, and leaving too late).

A hungry girlfriend stressed about a meeting was all it took for me to make choices I never would with a stranger or a client. Something that looked easy and low risk very quickly became one of the most dangerous situations I have been in. At the end, it could not be walked out of, and it was made more dangerous by complacency with time management.

All because we wanted to make it home for dinner.

Expert Halo Effect

This effect happens when we admire or respect a hiking buddy or someone in our hiking group – they develop an invisible halo. Often, these ‘experts’ are not only highly skilled but also confident, opinionated, socially domineering and/or personable, influencing not only you but the entire group. When this happens, we can begin to rely on them without question and without raising concerns… but we may, in fact, have noticed something that they have not.

In some people, confidence can mask a lack of expertise. Do they know something you don’t… or do you know something they don’t?

After I’d been hang gliding for a decade, I was on launch in another state; the wind was, in my opinion, unsuitable. While I was standing on the ramp, a personable and articulate man arrived and confidently introduced himself; he was a pilot too, he explained. Conditions looked great and why wasn’t I launching? I immediately second-guessed my analysis; he was a local and would know conditions better than I did. I didn’t share the subtle effects that led me to believe dangerous turbulence might exist (I must be mistaken). I was about to begin setting up when I thought to ask how many years he’d been flying. “Oh, I’ve only just started. I don’t have my licence yet!”

Flying at the same site on a better day. Do you have a good Expert Halo hiking example that could replace this flying story? Please contact us!

Just because someone seems to be an expert – or even is an expert – does not mean their decisions are invariably error-free. Always voice your concerns and questions: any good leader or buddy should welcome them. If they do not, you might be in the wrong group.

First Tracks aka Scarcity Effect

The scarcity heuristic is incredibly powerful, and is often the cause of the first poor decision in the chain leading to disaster. It’s when we value something more because it is less readily available. ‘Collector’s Items’ and special editions fetch disproportionately high prices because of this FOMO heuristic, but how does this apply to hiking?

For most of us, hiking is a recreational pursuit. Holidays occur in short windows of opportunity and you may not have the chance again or for a long time. Perhaps you’ve spent a lot on flights, site bookings and/or gear, all of which elevate the hike’s value in your mind, so that when you are at the trailhead with an increasingly terrible forecast, all you can think about is that wasted time, money and effort if you bail now. Everest is an infamous example where climbers have invested tens of thousands of dollars and months of preparation to summit in a tiny window. You may not be on Everest, but you are at the trail head, wanting to set off, and the same heuristic applies.

In good weather, the Tour du Mont Blanc is moderately challenging for average hikers like Geoff and me. For most people it is also a bucket list hike, and booking the huts is competitive and expensive. However, the terrain means that, in bad weather, anyone who has booked a tour or accommodation may need to skip certain sections and catch a long bus diversion through the valleys instead, or take a less interesting lower route alternative. We were lucky with the weather — the above image is just mist rising from the valley floor — but I confess that it would have been extremely tempting to stick to the spectacular route elsewhere even if the weather turned.

There are several ways to make better, more objective decisions. First is simply to acknowledge this heuristic and to be aware that it is influencing your decisions.

However, the best solution is to build exit points into your hike plan before you even leave home. These can be based around known risks for that particular hike including weather, terrain, gear and your own physical and mental condition.

For example, you know that you need to cross a river. Decide your safe margin ahead of time, not at the river. If when you arrive the river is obviously flowing faster than a certain speed (usually walking speed) and/or is beyond a certain depth, you will turn back without crossing, find another crossing point that meets your requirements, or wait for the river to subside. If it is borderline you may begin to cross but, if you reach your predetermined depth, you turn back rather than continuing to cross. Or, you can define ‘borderline’ as a hard exit point. Water crossings are high risk, and your desire to hike the track does not change the risk. Don’t allow desire to influence your decision.

Or, you know the track will become almost impassable or impossibly slow in extended rain, so you set an exit point: you will turn around if your pace is below X, or you won’t even go to the trailhead if the forecast is bad. Instead, you will have a Plan B. Sure enough, you arrive in town and the forecast is abysmal. Without a Plan B, you will be sorely tempted to leave anyway.

Approaching Frenchman’s Cap summit

These decisions are often made long before life and death situations; they often seem minor, almost silly. We applied this on Tasmania’s Frenchman’s Cap Track earlier this year, when we decided to stick to our plan and NOT summit on a clear day, even though conditions might deteriorate the following day; many hikers we met advised us to grab today’s opportunity. One hiker told us a recent group had spent five days waiting in vain for the peak to clear. But I was very tired and, though it was only a few hours past the hut, it also had the most challenging (for me, perhaps easy for others) scrambling of the hike, and we would have to come back down as well! We stuck to our plan and were lucky to summit the next day in perfect weather. However, in unsuitable conditions, we would have taken a different, lower track a short distance along Lion’s Head: we had a Plan B already in place.

Challenge is relative to your skill and ability. Although others could do this with their eyes closed, I’m glad we tackled this section with plenty of time and when I was fresh.

We had a lot of scrambling, but it was enjoyable and made safer because we didn’t have to hurry or return in the dark.

Sometimes the decision is a no-brainer. In Mt Field National Park the same month, we arrived at Park Head Quarters only to be told 100km/h winds were forecast in the highlands where we would be hiking and camping the next day. What were our Plan Bs? We could hike a lower route, delay, or go elsewhere. We ended up delaying but, if we’d been under time pressure, we would have hiked the lower reaches instead. Build Plan B’s into your agenda wherever possible especially if you have made big investments in time and/or money: not just different routes or turnarounds on the same hikes, but a different hike in the same Park, or even a hike in a different park altogether. This flexibility becomes easier with practice.

Approaching Cleme’s Tarn in Mt Field National Park. With the correct gear we made the decision to camp at altitude but, when gear fails or is inadequate, you may need to reconsider your plans:

-

Although I'm not sure how long it takes to get frostbite, I thought I was close on a recent hike to Mount Field. 0C at the top with 25-30 knots and the associated windchill. I didn't get frostbite with drenched gloves, but it was a close call at my level as I'm just a beginner hiker and very new to the snow here in Tassie.

With darkness arriving so early in winter, we ended up night hiking. I fell twice, partly due to fatigue and cold, partly due to the wind pushing us about, and partly due to poor visibility.

That really woke me up to be aware of how serious winter hiking is for beginners who don't know what clothing to bring, and without spares.

Social Proof Effect aka Social Facilitation

Humans are evolved to be social creatures: when we see other people doing something, we assume it is okay for us to do it too, especially when we ourselves are unsure in unfamiliar or ambiguous situations. The more people we see doing it – crossing a potential avalanche field or swollen river, hiking to a peak in a bad forecast, following a dodgy route, standing outside safety railings for the best possible selfie… the more we think it will be okay for us to do, too.

But of course, just because other hikers are doing something, does not mean it is appropriate for you to do the same. They may have missed something dangerous and should not be doing it themselves. They may have more experience or fitness, or different equipment, or be more familiar with the location. On straightforward hikes in benign weather, you can be reassured that thousands of ordinary hikers have done the same but, in challenging conditions and terrain, retain your situational awareness and assess each hike and decision relative to your own parameters and the environmental conditions you see.

Biases

Biases can arise out of heuristics or separately. Either way, they are systemic failures in logical thinking and lead to less objective decisions.

The optimism bias is when we believe that bad things that happen to other people will not happen to us. We all have it to some degree, or fear would paralyse us into inaction every time we stepped outside. However, when making decisions in high-risk situations, it’s important to logically consider this question: why will it not happen to us? Overestimating our own capability makes us mistakenly believe we’ll be successful where others failed. Unless you have good reasons – think ‘top level athlete’ – it’s wise to assume that you are no better than anyone else.

Exposed formations made famous on social media often have associated deaths because hikers fall from them. Many of these hikers have no climbing experience or skills, but nevertheless believe they won’t fall. And how many times have you seen those selfies on the very edge of waterfalls?

Confirmation biases are when we give precedence to information that reinforces what we want to be true, rather than what is true. We make decisions based on the summit in sunshine, ignoring the black clouds rolling in. We all have different risk tolerances but, wherever we fall on the spectrum, our decision will be more objective if we take both sun and cloud into account.

The Anchoring Bias is when we give precedence to the first piece of information we receive, and less weighting to subsequent ones. Changing forecasts and track conditions quickly make earlier assessments and decisions obsolete. Remain flexible in your thinking, and in your plan replace old information with new in your decision-making.

Other Physical and Emotional Human Factors

We all know that when we are tired, hungry, sick or have had a few too many drinks the previous night, we don’t perform as well as usual. This won’t matter on a stroll around the block at home but, on challenging hikes, we’re most likely to succeed if we are well-fed and -rested, fully recovered from any illnesses, and recreational drugs and/or alcohol have left our system.

Emotional factors can have an equally significant negative impact on good decision-making even before our hike begins. Relationship breakups, deaths of loved ones and other emotional upsets mean it’s unlikely our full attention will be in the here and now.

When we are under pressure on trail, such as a storm in an exposed location, or we are exhausted or cold, it is much, much easier to make mistakes: half of our mind is on finding shelter rather than the task at hand. Panic, or even just adrenaline and nerves, impact clear thinking. When we are hurrying and under time pressure or even only somewhat stressed, we are more likely to overlook important considerations when making decisions:

As MyLifeOutdoors explains, the more extreme the situation, the more important it is to think and work methodically, though of course this is easier said than done! When we are wet as are Steven and his mate in the above video, the temperature doesn’t need to be very low for hypothermia to set in. When should we set up the tent? (Image Credit: Screenshot from MyLifeOutdoors)

Complicating other obvious physical effects of exhaustion, hypo- or hyperthermia, are the equally impactful effects on the brain. When our bodies cool below or rise above a certain temperature range, we are simply unable to think; it’s why people suffering from hypothermia are sometimes found naked and frozen because they’ve taken off their clothes, and why hikers dead from dehydration and heatstroke are found with half-full water bottles in their packs. Decisions must be made before you are no longer able to make them: by the time you are in real trouble, you lose the ability to make rational choices. Worse, you won’t know you’re no longer rational. Reader Colette Edings points out, “Three times I've seen hyperthermia in hikers and none of [them] were aware that they were anything but normal. They denied there was a problem.”

Gammon Ranges, South Australia. Hot and dry even in winter, with big water carries.

Tidemarks on Geoff’s shirt tell the sweaty story at the end of this hike! Some days we carried 9 litres between us because we weren’t confident of water sources.

However, before then, we can mitigate these human factor effects through practice, routines and physical/mental checklists.

For example, regardless of weather, Geoff and I each walk around our tent before we get inside it (if you are a couple, you must both do it, or one do it all the time: you can’t swap around). We check every stake and every point that needs assembly. This practice is helpful because, when we are in difficult conditions, conscious, repeated routines and checks are more likely to ensure we work methodically.

In other situations, unless we are under imminent threat there is always time to pause and think. Take five deep, slow breaths, eat a gummy bear or jelly snake, have a drink of water. Analyse the situation, consider your options, choose one and then act on it. Re-evaluate often as the situation changes because you may need to repeat the process multiple times. A framework for assessing risk and determining actions is a huge topic that deserves its own article (in Part 2!).

Human Factors Act Simultaneously

On a single hike, not one but multiple heuristics, biases and other human factors act in tandem on our decision-making.

Hiking Cradle Mountain with Geoff… we’re doing it the right way (for us). Unlike my first time!

Decades ago, I hiked Cradle Mountain solo at the tail end of a work trip. I had little time before my flight the next day, little hiking gear — a light rain jacket, no first aid kit or head torch — and this was in the days before PLBs. I’d driven a long way and was on a high from a successful week of work.

I started late (the ranger had said okay: even then I was a slow hiker, but didn’t look it; I figured he’d know though as he was the Ranger) and met only people coming back the other way. The last ones mentioned no one else was up there. I was sure I could make it. The rocks became increasingly slick and icy under my sneakers. The last scramble was finally too much and turned me back. Legs shaking, I hopped icy boulders with metres-deep gaps: as in the Dolomites, only luck prevented injury. We all have stories like this and only realise in hindsight how easily things could have gone differently.

Competitions are infamous for the way they combine and exacerbate heuristics and cognitive biases, resulting in not one but many competitors making poor decisions. Most competition organisers recognise this and almost always include strict protocols and checks specifically to keep competitors safe from poor decisions:

The perfect start early on Day 3 of the ultramarathon near Queenstown, New Zealand… (Image Credit Alex Noon)

… not so much perfect later. Six competitors were taken out due to hypothermia. (Image Credit Alex Noon); Alex’s Strava

-

This happened in the South Island of NZ in February 2023 whilst I was participating in the Southern Lakes Ultra multi-day race. I'm more of a 'back-of-the-packer', as were many of the participants, who were also mostly female.

We started Day Three at 7am with three steep mountains to climb. At dusk – around 7pm – when it cooled down, I put on my down puffer jacket. An hour later, it started to rain so I put my rain jacket on over the puffer jacket.

Around 11pm on the run (read hike: our pace averaged 3kph), an ex-nurse/fellow runner told me that I was suffering from hypothermia as I was ‘all over the place' and losing my balance. She ensured I walked between her and another competitor so that they could keep an eye on me. Despite this, whilst descending the final mountain, I slipped on an embankment and couldn't get back onto the track. The two women stayed with me.

An hour later, two more competitors caught up and were able to pull me back onto the track. By this time I was truly hypothermic.

We donned bivvy bags and set off two PLB's and a Garmin Inreach Explorer for the three of us. Eventually, someone arrived from camp to help one competitor to continue to camp, the other remaining with me. Two more experienced mountaineering women, including the Race Director, helped me onto a safer, wider bit of track for evacuation by chopper.

At dawn, two choppers started circling, one picking up another hypothermic competitor not far from me, before I was winched into the other chopper along with yet another hypothermic male competitor. All up, six hypothermic competitors were evacuated from the mountain by chopper.

It wasn't until I was in Queenstown Hospital that I realised my rain jacket had failed and my puffer jacket was wringing wet. We had only been in fairly light rain for about four hours and were not moving fast enough to work up a sweat in the cold weather. My temperature was recorded as 34.7C at the hospital but was probably lower than that on the mountain.

Takeaways:

1. Test rain jacket properly.

2. Wear synthetic warm thermal top instead of down puffer jacket

3. Remove clothes that are wet before getting into bivvy bag.

4. (Done): Carry a PLB and Garmin InReach (with subscription!).

5.( Done): Carry spare thermals/clothes in a drybag. Another rescued hypothermic competitor did not use a drybag so put on an already wet down jacket.

I survived and, after a day's rest, successfully completed the last 2 days of the event.

ED: Can you think of additional decisionmaking strategies to avoid or mitigate this event?

Take Away Points:

If all the above was TLDR for you, here is a summary.

Planning for a Challenging Hike:

Know distances, elevation gains and track conditions before you go.

Seek a range of reputable perspectives and listen to locals.

Be realistic about your abilities, don’t over- or underestimate them!

Refine, develop or practice any special skills that you might need.

Build flexibility into your hike, for example:

Include bail out points/exit strategies.

Where possible, include a lower or easier alternative to the haute or difficult route you’ve planned

Carry extra food/water should you be delayed or misjudge pace

Establish objective decision-making criteria or exit points for your hike, for example:

depth/flow at water crossings

Turn back/stopping points

Untenable weather conditions

Before your Challenging Hike:

Systemise your approach to setting up and checking equipment.

Ensure you are familiar with your gear.

Practise setting up your tent and using other gear in poor conditions.

Systemise your approach to decision-making.

On the Challenging Hike:

Understand that heuristics and cognitive biases can negatively affect objective, rational decision-making.

Stick to your decision criteria, unless the situation differs significantly from your expectations (eg a rope is unexpectedly provided at a water crossing).

Adhere to your hike plan unless it is unsafe to do so, or new information becomes available.

Use your systemised approach and cross check important items of equipment setup.

Trust your instincts: if something seems wrong stop and re-evaluate the situation before pushing on: our subconscious may have noticed something untoward.

Voice and discuss your concerns with others (where possible).

Test your decisions by using ‘what if’ questions.

Be patient if conditions are poor; allow and take more time and care even when your desire to scramble into the tent or to push on is high.

Build in an extra day for contingencies: views and enjoyment will only be there if you are alive!

Review how you are progressing multiple times during the day/hike and adjust expectations accordingly.

Listen to others but hike your own hike and make your own decisions!

Do you have any hiking stories that reflect what is discussed in this article? Please share in the comments, or contact us with an image or two and a short description to include in the article or a linked article (anonymously if you prefer!) as a real-life example. Caro Ryan’s ‘Rescued’ podcast also has many useful and informative examples from which we can all learn.

Stay Tuned for Part 2: Making Better Decisions when Hiking, with a practical framework for risk assessment and decision-making!

A huge thank you to current and past outdoor educators and/or guides EL, John J, John McLaine, JP and Lisa Murphy (Big Heart Adventures), as well as psychologist KH and Dr Nicole Anderson MD (General Practice, Wilderness/Expedition Medicine) who checked and contributed to this page for accuracy and relevance. An equally huge thank you to Alex Noon, Colette Edings, Jack, JB, Martin, Sarah and Yvonne for generously sharing your stories and thoughts: it’s your anecdotes that flesh out the dry theory and bring it alive for readers.

The reward of a safe and successful summit… and descent!