Understanding Weather Forecasts and Apps when Camping in Strong Winds and Storms*

Weather forecasts are essential when planning hikes, but do you really understand what a strong wind forecast means? At what elevation? Is it an average? Mean? Gust? If a gust factor, by what percentage? What is the Beaufort Scale and why is it so useful? What is wind chill? Why do apps have different forecasts and which one is the best for your route? Read on for answers!

*This article is a companion to

· Tents in Strong Wind: What You Need to Know,

· Tents in Strong Wind: Terrain and How to Choose the Best Pitch and

Benign conditions in the highlands of Australia. Camping here requires a good grasp of weather forecasts plus the right tent for the conditions you expect. The 3-season Mont Moondance suits this weather, but you’d choose the Mont 4-season Dragonfly for tougher conditions and longer trips in alpine regions. Image Credit: Geoff Murray

Understanding Wind Forecasts

When you live in a region regularly subjected to extreme winds, you’ll have a good handle on what strong wind forecasts mean. However, many of us in mild climates do not, especially when extrapolated from the comfort of our home to an exposed hillside at altitude in a tent. It’s therefore important to understand the forecasts you’re relying on well before your week away.

Strong winds forecast for South Australia. (Image Credit: Australian Bureau of Meteorology)

The Australian Bureau of Meteorology provides a good summary of criteria they use for wind forecasts and warnings. Other countries’ weather bureau websites provide similar information so it’s worth checking what they really mean when they issue forecasts. Below we reproduce the most relevant parts of BoM’s summary for Australian hikers.

“Wind is made up of gusts and lulls. The Bureau's forecasts of wind speed and direction are the average of these gusts and lulls, measured over a 10-minute period at a height of 10 metres above sea level. [And remember, we’ve seen that wind speed increases with altitude due to shear effects]. The gusts during any 10-minute period are typically 40% higher than the average wind speed. Thunderstorms and squalls may produce even stronger gusts.”

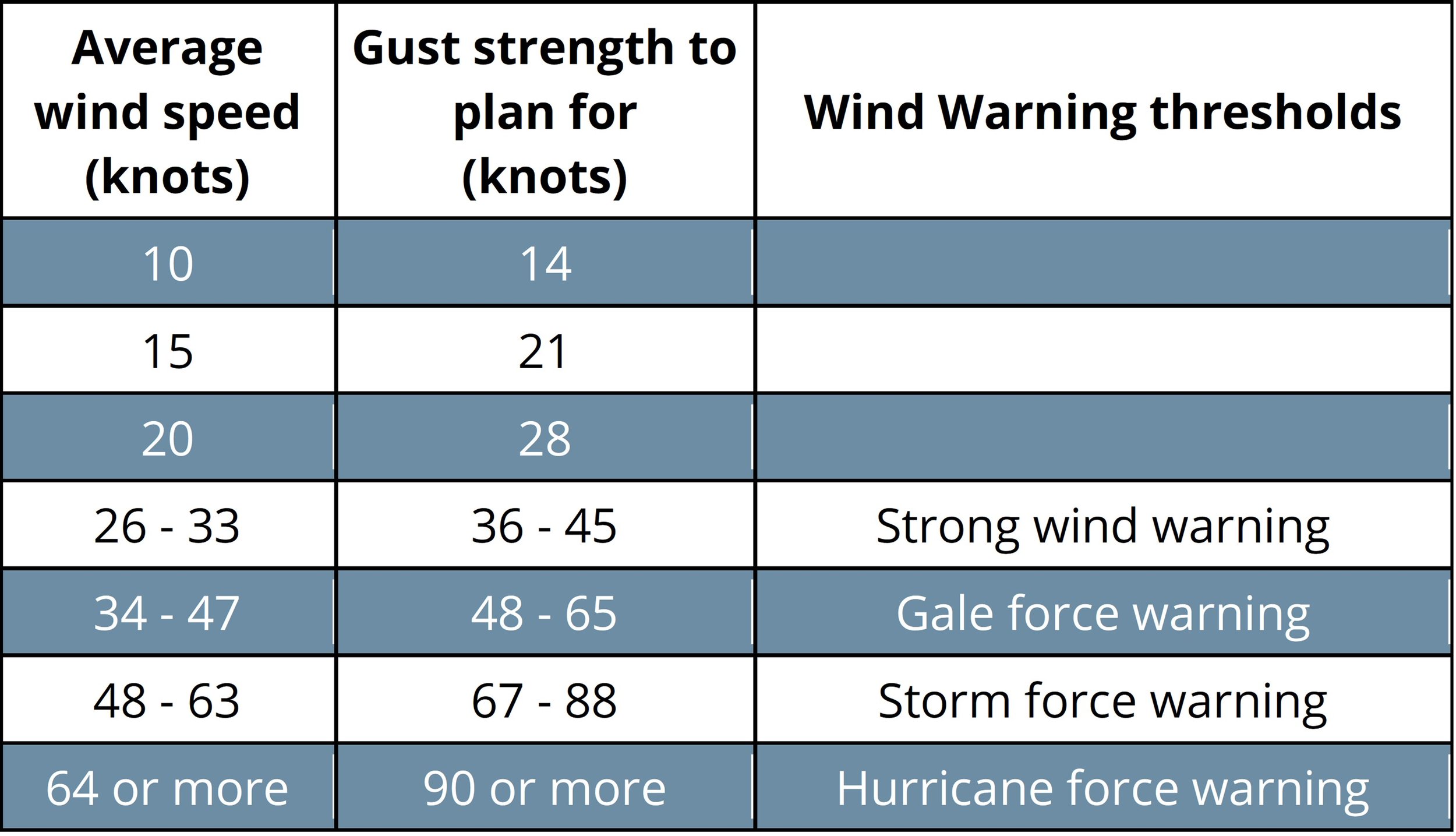

Based on the 40 per cent rule, the table below shows the potential gust to expect for different forecast average wind speeds/wind warning category.

Source: Bureau of Meteorology Australia

They also remind us that gusts from thunderstorms may come from a different direction than the average wind direction.

The Beaufort Wind Scale

Fig 1: The Beaufort Wind scale classifies wind speed into categories.

The Beaufort wind scale measures wind speed according to the impact wind has on land and sea. Although the system is old, it remains convenient for describing wind speed today. The table below explains what can be expected for each level and its relationship to forecast average wind speeds. The Beaufort Scale is particularly useful because it is widely used worldwide, so we all know what is meant in different countries even if measurement units are different.

Fig 2: Here is what you would expect to see and experience in various wind speeds (Image Credit: Australian Bureau of Meteorology)

Fig 3: And here’s Geoff’s nifty conversion graph between knots, metres per second, mph and kph. Or, to convert knots to mph multiply by 1.151, to convert to kph multiply by 1.852, to convert to m/s, divide by 1.94384. Image Credit: slowerhiking. com

Wind Chill

Wind chill is a measure of wind speed as a coolant on our skin. The higher the windspeed, the more the cooling effect; frostbite happens when your skin’s heat is lost faster than your body’s ability to generate it. Frostbite is less common in Australia’s relatively warm temperatures, but windchill can hasten hypothermia in our and New Zealand’s alpine areas and, of course, also in the Northern Hemisphere. In these regions, it’s essential to factor in wind chill when planning hikes, particularly in the choice of clothing and tent, when a drafty single wall design may not provide sufficient protection.

We rarely see wind chill forecasts or tables in Australia, but it’s worth understanding them if venturing into alpine areas in winter. The coloured areas indicate the different times for frostbite to occur on exposed skin but, for Australian and New Zealand readers, hypothermia in the pale blue zone is the more common concern.

Many weather apps and Weather Bureau sites refer to the effects of wind chill as “Feels Like” in their presentation of the information.

Why is Understanding Weather Useful for Hiking?

Literally gale force winds on Western Australia’s southern coastline near not so Peaceful Bay. Gusts knocked us sideways.

Understanding local weather, rather than just checking the forecast, is enormously useful when hiking.

A simple example is our hike from Peaceful Bay to Boat Harbour on the 1,000km Bibbulmun Track in Western Australia. We’d been buffeted by gale force winds along the five kilometre coastal stretch leading into Peaceful Bay and heard there was a similarly strong wind warning issued for the next day, which included a 300 metre canoe paddle across a tidal inlet. We therefore aimed to reach the crossing very early to beat the strong upper-level winds mixing down to ground level via the increase in thermal activity that happens during the day: we knew it would likely be calm early in the morning.

We crossed in light winds that were already beginning to strengthen by the time of our sixth trip across (we were having fun and returned a few extra canoes!). After the crossing, we elected to take the inland route to Boat Harbour rather than walking along the beach in those winds again.

Winds are calm now, but the crossing will be almost impossible later in the day.

Understanding weather is also particularly useful in predicting localised wind direction changes when setting up your tent in anticipation of a storm. Winds associated with storms can be unpredictable, but you can often make a pretty good guess if you’re familiar with local weather, which often follows a consistent pattern. In our hometown, wind direction changes follow an anticlockwise pattern. Local seabreezes are southwesterly, and continental seabreezes in summer are southerly, strengthening around 4pm. Strong winds associated with fronts are usually southwesterly. Gust fronts associated with rain come from the direction of the storm. Countless other patterns exist in regions round the world. Locals are usually familiar with these patterns, so don’t be afraid to ask if you’re visiting.

Weather Apps

We understand that many people have their favourites so feel free to skip this section but, if you want to understand where they source their information for forecasts and why some are more reliable than others, read on.

There are numerous weather apps for your phone. Functionality varies, but most rely on the same global data sets and weather models. Some apps access local “infill” private data that makes them more accurate, but that depends on your location, and they often require paid plans. If you’re hiking remotely, infill weather station data for your location is less likely: actual conditions reported by apps are taken from the nearest available weather station.

The most common model used to support weather apps is the GFS or Global Forecast System. It’s free and is run by the National Centers for Environmental Prediction, an arm of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration of the United States Government.

The GFS model data is summarised 25 km gridded data, which simply means that there is one modelled data point for an area 25 km by 25 km. Other global models such as the ECMWF (European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts) use a 9 km by 9 km grid, so have a much higher resolution. This is particularly useful in areas with mountain ranges, where low-lying areas will be different to the higher elevations. It is not free, so is used less often in online weather apps.

Strong winds forecast for Tasmania. Weatherzone has an app utilising ECMWF. Note they cite ‘10m wind gusts (instantaneous)’. Familiarise yourself with the terminology used by your favourite source. (Image Credit: weatherzone).

The same information is usually provided by national weather bureaus. They utilise global data sets most reliable for their forecast area, whilst also making localised corrections/adjustments. In Australia it’s the Bureau of Meteorology’s MetEye; the United States, the National Weather Service - Graphical Forecast. Forecast data sets are typically updated at least twice daily.

Many apps have excellent interfaces (particularly for phones), and some let you choose the global model used for the forecast. Some apps switch between global models and the one expected to perform best in your location. You can use these globally; ideally you should compare forecasts from one or more apps with the official weather bureau forecast for your location.

Geoff prefers Predictwind. The free service provides seven-day weather forecasts for up to two locations. You can change locations as you move around the country or world. The paid version allows more locations and has more features. The free version provides all we need with access to four different global models plus two of Predictwind’s own models. Others we’ve used include: Willy Weather (Australia) and Weawow. We also tried Accuweather but it didn’t perform well for us in areas of Australia and Europe. It may do better elsewhere. If possible, check your app in the area before starting your hike.

Even better, start playing with your app a month or two before your trip. Familiarity with an app helps you to get the most out of it, knowing which models provide the best results for different winds and locations.

Because we are often out of cell range, we check forecasts several days ahead whilst in range, and get updates on a Garmin InReach when hiking. The Inreach utilises forecast information from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, so it probably uses the GFS model forecasts as input data (which predicts weather conditions at a 25 x 25 km resolution).

The image below illustrates the importance of model (and hence forecast) resolution.

Different wind predictions (in knots) for the same time from different global models: ECMWF on the left (resampled and presented at an 8 km grid) and GFS utilising a 25 km grid on the right. (Source Predictwind). Given the models use much the of same climate data, the higher resolution model should usually provide a more reliable forecast.

Irrespective of what app you use, the supporting model(s) present an average of weather conditions across an area, and characteristics that might influence wind speed (eg ground elevation, terrain, ground cover) are also averaged. So, although apps provide more reliable information for your location than regional forecasts, they still lack sufficient resolution to accurately represent your specific location. This is why uderstanding the interaction between tents, terrain and wind as covered in Parts 1 and 2 of this series is so important.